November 16, 2020

By Casey Adams, art by Robert Martinez

Wind River Country artist Robert Martinez is on a mission to adjust your expectations. Of Native art, of Native Americans, of art as a whole.

“Having grown up on the [Wind River Indian] Reservation, and being part of the Northern Arapaho tribe gives me an outlook on how people view Natives and how professional non-Native artists use Native imagery,” Martinez explained. “There’s often a romanticized or stereotypical version of what they paint—you know, Indian on horseback, stoic, in a mountain setting … an Indian princess with wolves and some feathers.”

Martinez—Northern Arapaho, Latino, and Anglo—doesn’t do that.

“I want to depict something that’s true to us but also is what I consider an abstraction.”

The most dramatic way in which he turns the expected inside-out is the loud color in his acrylic-and-oil paintings. Monochromatic and dual-chromatic airbrushed portraits catch viewers’ eyes and stare at them, forcing them to confront the stories behind the paint.

“I had an instructor who told me, ‘Never use pure color.’ Well, you can see I listened to that,” Martinez chuckled.

In his latest series, Martinez’ subjects look boldly out from under headdresses. Not your typical feathered representations, they are lined with wifi, cellular data, and Bluetooth-connectivity graphics. The faces are dramatic shades of purple, red, green. Martinez titled the series “Strong Signal” and sees it as a tool for starting important conversation about the Native issues that he finds people have an inclination to separate from Native art. “The NODAPL stuff … and Keystone—we’re always talking about mascots … you’re always seeing that stoic Native face,” he said, but the stories aren’t being processed. “So you get these signals on your phone—you’re putting out a strong signal but you’re not listening, you’re not seeing.”

“The NODAPL stuff … and Keystone—we’re always talking about mascots … you’re always seeing that stoic Native face,” he said, but the stories aren’t being processed. “So you get these signals on your phone—you’re putting out a strong signal but you’re not listening, you’re not seeing.”

Another series of paintings in the same brightly colored style puts forth Captain Native America, Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman.

“In Indian Country we don’t have a lot of highly visible heroes. So I created a whole series of Native super heroes,” Martinez explained. It will reside in the permanent collection at the Red Cloud Museum in South Dakota, adding to the long list of museums, art galleries, and art shows across the nation who display his work.

“In Indian Country we don’t have a lot of highly visible heroes. So I created a whole series of Native super heroes,” Martinez explained. It will reside in the permanent collection at the Red Cloud Museum in South Dakota, adding to the long list of museums, art galleries, and art shows across the nation who display his work.

Martinez’ portraiture isn’t typical or realistic, but they guide the viewer to a fresher understanding of his Native American subjects. He’s interested in the story behind the story and in painting that story behind the face on the canvas.

“I heard from a priest or a pastor or one of my elders something to the effect that if God or Creator gives you a talent, it is a shame—if not a sin—not to use that talent,” Martinez said of the story behind his face, the motivation behind his brush. “So I have this talent, and if I don’t do something with it—and even more to the point if I don’t use it to speak about something, that’s a waste.”

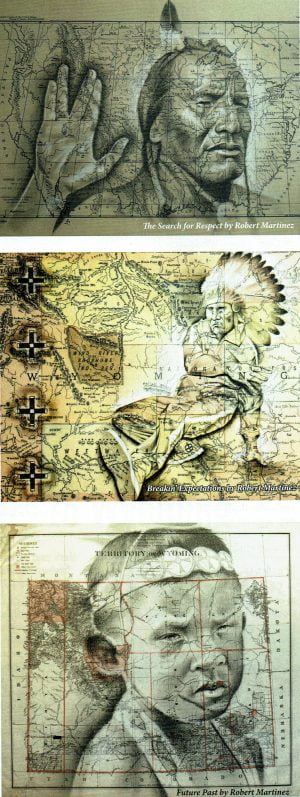

Martinez has also injected his contemporary commentary into the genre of ledger paintings, a style which, by its very nature, demands an eye on history’s truths. In the late 1800s as Native Americans were being migrated to reservations, they couldn’t hunt in the way they had before, and in turn they couldn’t paint their stories on hides in the winter. Instead, they turned to trading for old ledgers to paint upon. Rather than the more traditional flat figures that remain popular to this day, Martinez reminds his viewers of who America’s Natives are today.

Martinez has also injected his contemporary commentary into the genre of ledger paintings, a style which, by its very nature, demands an eye on history’s truths. In the late 1800s as Native Americans were being migrated to reservations, they couldn’t hunt in the way they had before, and in turn they couldn’t paint their stories on hides in the winter. Instead, they turned to trading for old ledgers to paint upon. Rather than the more traditional flat figures that remain popular to this day, Martinez reminds his viewers of who America’s Natives are today.

For example, on an old map, with the Wind River Indian Reservation outlined near-center, Martinez has drawn man in a track suit and headdress breakdancing on Wyoming territory.

Working his way through a stack of his contemporary ledger-style pieces, Martinez pulled out another, black text on off-white paper with an added sepia-toned illustration:

“This is on ‘Laws Relating to Indian Affairs,’ so you turn that upside down and then you draw all over it,” Martinez said before moving on to a land grant document augmented by his hand with the face of a Native child. “This is me putting an actual face on that.”

His dedication to his craft and his people is paired with dedication to his family. His youngest daughter, 7, spends her days with him, and she and her big sister, 10, join him in his studio for their own crafts.

Social media has become a powerful utensil to that end, and you can engage in his conversations on Facebook and on Instagram.

Better yet, you can purchase his art at www.martinezartdesign.com and play a role in adjusting expectations. “Non-Native artists painting Native images have better careers and make more money painting those images and perpetuating those type of thoughts than actual Natives doing the same work,” Martinez observes. “I’d think that a collector who wants Native artwork would lean more toward a Native artisan.”

Martinez’ studio is open to guests by appointment, and you can find the extensive list of installations of his art across the U.S. and examples of his work on his website, www.martinezartdesign.com