October 14, 2019

By Lois Wingerson

These days, Carol Petera of Dubois spends most of her time gardening, quilting, playing bridge or cribbage, and visiting friends. It may sound like the relaxing routine of any typical retired woman in Wyoming, but that’s deceptive. She is hardly a typical retired woman.

Asked to describe what Carol has meant to Dubois, former mayor and close friend Twila Blakeman quickly offers up a list: After moving there to retire, Carol promptly began using her 18 years’ experience and contacts in state government to the town’s advantage. She won $150,000 in a federal grant to 10 Dubois nonprofits through then-Wyoming Representative Barbara Cubin. She spent 13 years promoting and managing the town’s conference center, used her considerable persuasive skills to impel a reluctant state agency to fund a new library for Dubois, and worked to amass $2.5 million in grant funding so that medical facilities and a fire-fighters’ training center could rise on the site of the former sawmill. After that, she was the driving force behind the new assisted living facility.

If Carol had not moved to Dubois after retirement, in effect, it might not be the town it is today.

It helped that she married a man who became director of the Wyoming Game & Fish Department.

“Most of my story was about Pete, and living with him was a moving experience,” she says with a twinkle in her eye.

His job took them all over the state, and she came to know nearly everyone in state government personally. But her influence went far beyond merely hosting dinner parties for her husband’s colleagues—although she also did that.

“She has a tenacity about her, a quiet approach to people that is very persuasive,” remarked Max Maxfield, former Wyoming Secretary of State. “She cared deeply about what she was doing, and she cared deeply about Dubois. She knew what she wanted, and she had a lot of credibility because of her track record.”

Born on her grandparents’ ranch near Sundance, Carol has a storybook Wyoming history. Her grandmother did what other pioneer wives had done: She claimed the 160 acres neighboring their homestead and ranched those herself. Her son Harry Reynolds, Carol’s father, worked as a cowboy and married a schoolteacher, her mother Charlotte.

Carol was the last child of their marriage, the youngest of eight after a 10-year gap. (“Technically an only child,” as she puts it.) The undivided attention of older parents allowed ample time to learn family history.

Once, Carol joined her mother to visit the grave of a sibling she never met: an older brother who died of whooping cough at three months of age. As a young mother herself, with her own baby on her hip, she suddenly saw her mother with different eyes.

“How on earth did you manage?” she asked.

“I had a feeling when the time was coming,” her mother

replied. “So I bathed him, and dressed him, and then rocked him and rocked him

until he was gone.”

As a child, while her parents were feeding stock in the morning, Carol would

make breakfast on a wood stove (which now sits in her dining area). Afterwards,

she would mount her horse and ride four miles to a one-room schoolhouse. On

days when those were a very cold 45 minutes in deep snow, the teacher would put

her feet in cold water and rub them.

In high school, Carol loved her studies so much that she graduated in three years. It was there that she met Francis “Pete” Petera, the son of a lumberman.

Once, Pete asked a friend to drive him out to the Reynolds ranch. They found Carol and her mother shelling peas, and sat down to help. “Pete said, ‘Now I know where you live’,” she recalled. “This still makes my heart stop.”

After a year of college, she went into nursing school. One evening, as an aide at the hospital in Newcastle, Carol heard a knock at the window. It was Pete, who had driven over from Spearfish S.D., where he was going to college. He told her he couldn’t live without her any longer and gave her a diamond ring.

They married the following year. Pete soon got his first full-time job, as game warden in Baggs, and the “moving experience” began.

They had three children by 1962, when Pete was transferred to Jackson. Carol recalls it as a small town where everyone knew everyone.

Back then, she said, being a game warden was a “family affair.” She and sometimes the children occasionally accompanied Pete on pack trips around his territory, which reached to the edge of Yellowstone National Park.

For her husband, protecting wildlife—which might sound like a fun outdoorsy job—was a heavy and sometimes risky responsibility.

“When you’re a policeman,” Carol observed, “there are usually two of you. A game warden is alone, and everybody you’re working with in hunting season carries a gun.”

During those years Carol worked in a bank, then in the office of her children’s school. She won a seat on the school board. Eventually she worked as an elections officer for the Teton County Clerk, which was very important for her future.

After 13 years in Jackson, they were transferred to Saratoga, to Cody, and finally to Cheyenne. Pete had been appointed assistant director of the game division in the Wyoming Game & Fish Department, and eventually rose to become director of the entire department.

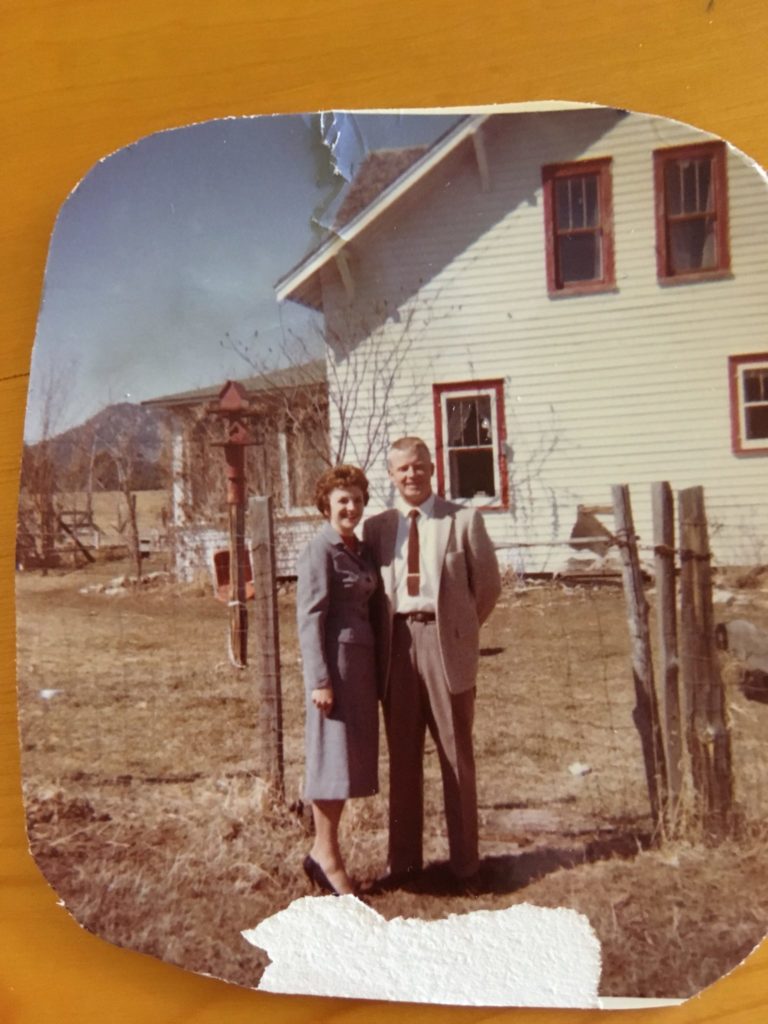

Carol and Pete outside their home in Sundance, Wyoming

The capitol city brought a “whole new lifestyle,” Carol said, because “there were public expectations of us.” Pete had business travel, not pack trips. They were both working with legislators, Pete concerned with laws about animals and Carol, drawing on her experience in Jackson, with laws about elections.

She now had a job as chief elections officer for the state of Wyoming, which lasted through several governors’ terms. After one change in administration, Carol became a fiscal and personnel officer in the Department of Audit, offering her new contacts and insights into state funding procedures.

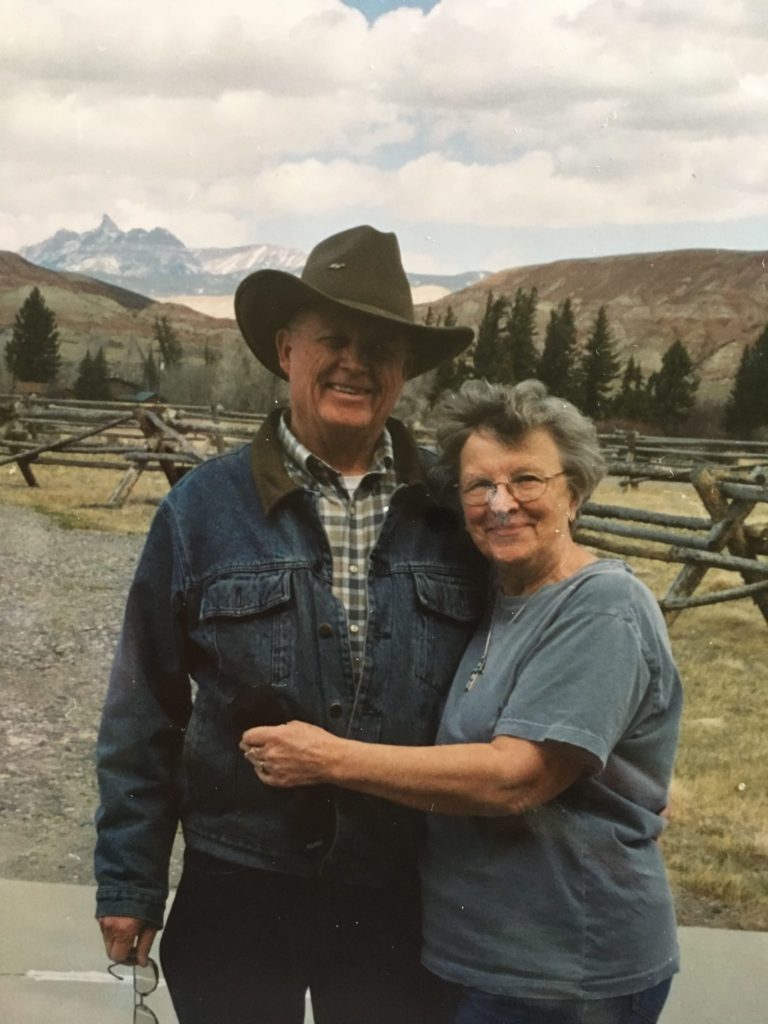

Initially the couple had planned to retire to Jackson, but as the time approached their attention turned to Dubois, because Pete and a friend had taken annual hunting tips in the mountains nearby. The Peteras retired from government in 1995 and moved to Dubois, where they found property with a splendid view of the town’s landscape icon, Ramshorn Peak. Pete set about completing their new house and building fences. Carol entered the next stage of her career.

“Pete was just fine with that,” she remembers. “There was a lot to do. He was building the house.”

Twila Blakeman, who owned the campground in Dubois with her husband, said she was drawn to Carol because “she was so bubbly and friendly. You just kind of liked her the minute you met her.”

Within a year, Twila had lured Carol to the board of the new conference center, the Headwaters Center, and later to a job as its manager. She recalls that Carol got new furniture for the lobby and attracted donations, while persuading her contacts in state government officials to hold meetings there.

Soon after arrival, Carol learned of a special grant opportunity through the federal government. She founded a new nonprofit, the Dubois Community Project, in order to apply, and won $150,000 in funds for 10 other nonprofits in Dubois.

Also during those her early years in retirement, her last-ditch effort helped to rescue a project started by others from a crucial setback. A group of residents had spent years working to raise funds to replace Dubois’ tiny, antiquated library with a new building.

Friends of the Library had raised substantial funding locally, but there was no way the tiny village could fund on its own the entire cost of construction, nearly $1 million. The group was asking help from the State Loan and Investment Board (SLIB) for about 45 percent of the cost. Dozens of groups and institutions in town, as well as schoolchildren and other individuals, had written SLIB with letters of support.

On the evening before the SLIB committee was due to decide its next round of grants, Carol took a dispiriting call from a member of the library board. The application appeared to be doomed, because it wasn’t even on the agenda for that meeting.

Carol looked up the names of the five elected officials on SLIB (one of whom was Secretary of State Joseph Meyer, a close personal friend and regular visitor at their home) and called them all.

“People have worked so hard for this,” she recalls telling them, “and we really need that library.”

Later, Carol heard that one of the government officials kept winking at a library board member during the meeting. As it was about to adjourn, one of them spoke up.

“I don’t see anything here about the library in Dubois,” he said, “and I think this is very important.” Governor Jim Geringer added a word of support, and the grant was approved.

“I have no idea how this happened,” said the library board member, who called Carol again after the meeting. “But I know you were involved.”

Carol may be friendly, says Twila Blakeman, but she can also be “very forceful when she’s on a mission.” No accomplishment shows that more clearly than her quest to provide Dubois with an assisted living facility.

Carol was haunted by stories of older residents who declined and died alone because they simply wouldn’t leave Dubois, even though they had nobody to care for them. Others were exiled from their mountain ranches to nursing homes in some distant city.

Meanwhile, the ideal property for an assisted living facility, on the site of the former sawmill, sat abandoned. The Nature Conservancy, which owned the property, had already donated an adjacent plot of land for a new medical clinic. The Conservancy was all in favor of the idea, but it took many years to achieve the second property transfer for an assisted living facility. For reasons of their own, a majority of the Town Council was against the idea.

In meeting after meeting, “the vote was always 3 to 2 against,” Carol said.

Fed up with inaction on the project, the Nature Conservancy finally sent a representative to one of the Town Council meetings. The representative said she would not leave–would sit there all night if necessary—until the Town agreed to the transfer. The strategy worked, and the deal was made.

But the fight was just beginning. The Wyoming Business Council needed to approve funding for the facility. The Council rejected the idea, in part because (according to former mayor Twila Blakeman) they had never been approached with such a proposal. It didn’t help that an out-of-state consultant had said that Dubois was too small to support such a facility.

Nonetheless, Carol had her heart set on the idea. She was not an official member of the group that planned the future Warm Valley Lodge, but “she had to be in the middle, because she made all the funding decisions and had those connections,” said its chairman, Dick Hodge.

On the plaque outside the building, she is designated “project coordinator,” because as he puts it, that’s what she did. Her efforts went far beyond filling out grant applications. She visited every assisted living facility in the state to investigate best practices. She contacted the Wyoming Department of Health to obtain the relevant regulations.

One day (the ground was slippery, Carol recalls), she climbed a hill behind the proposed property and took a photo of the beautiful riverside location. Then she obtained from the local VFW Post a photo of all the retired military people in Dubois that had appeared in the local newspaper. She taped that to the back of the other picture.

Carol showed the photo to all elected officials involved in the proposed grant approval, and then she took it to a meeting of the Wyoming Business Council. When it was her turn to speak, she said, “May I approach?” and then showed them the photo. First they saw the property, with the river behind it and the new medical clinic next door. Then she flipped it over to reveal faces of all the aging veterans.

“Carol,” Governor Dave Freudenthal said with a chuckle, “you hit below the belt.”

She also remembers what he said at the end of the meeting. “I wish I could give you the whole $300,000 you’ve requested. But I do have $150,000 for you.”

In addition to a grant from the federal government, the rest of the money for Warm Valley Lodge was raised locally. When it opened officially on August 13, 2013, it was Carol’s hand that joined then-Governor Matt Mead’s to cut the ribbon.

Carol smiled throughout the ceremony, but that was another act of sheer determination. She went home afterwards, she said, and cried her heart out. It was a bittersweet triumph, because her chief advisor was not present.

Pete had died suddenly from a heart problem five months earlier, two weeks before their 60th wedding anniversary. Her profound grief truncated overwhelmed Carol’s spirit for many months, during which she turned her mourning into memorials—cutting squares from his many plaid Western shirts and crafting them into quilts. She gave most of them away to Pete’s grandchildren and other young people who had admired him.

Gradually, Carol has returned to her usual cheerful self, continuing her work with the Dubois Community Project and enjoying the company of friends. But she will never find a replacement for her best supporter.

“I can’t tell you how many times I wanted to quit,” she remembered. “ I would get home and be so discouraged. I didn’t quit, because Pete said, ‘You can’t. You’re the only person who can get this done.’” She was. She could. And she did.

Posted in Notes From the Field