August 11, 2023

This story was originally published by St. Stephens Indian Mission Foundation in VOL. XXIV APR/MAY/JUN 1994 NO. 2. St. Stephens Indian Mission Foundation owns the copyright, and the story is reprinted here with permission from the Foundation. More information on the Foundation can be found following the story or by clicking on the link above.

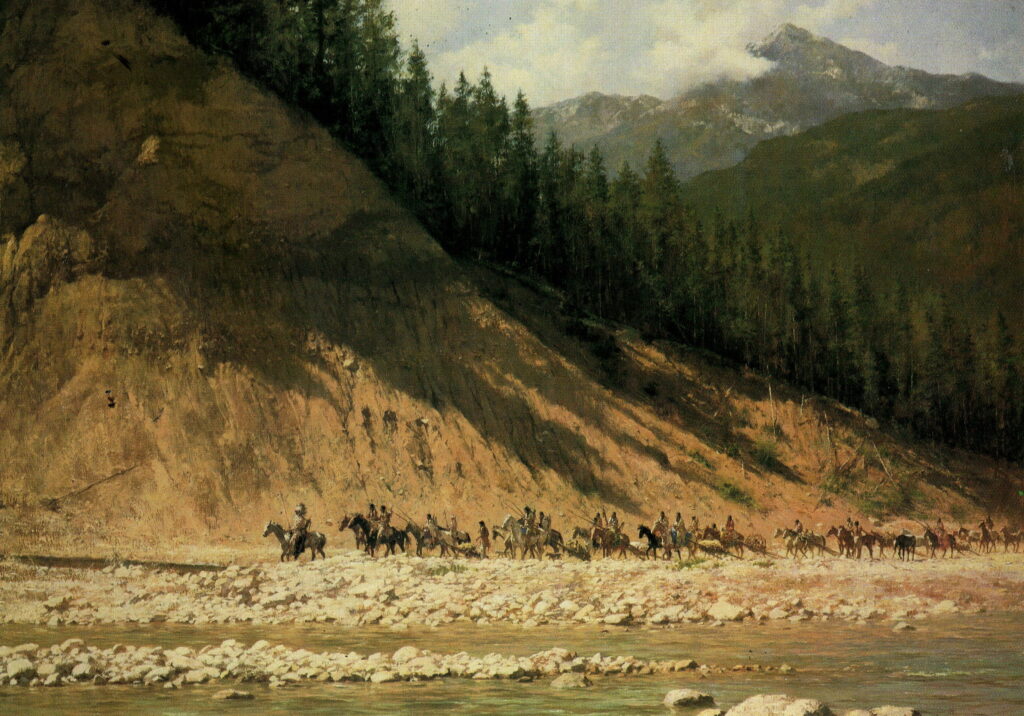

Beginning with the days of “Silent Pictures,” Hollywood movies have portrayed North American Indians riding on horseback. But in actuality, they have had possession of horses for a relatively short time. Indians were totally afoot when explorers came to North America. As these early Indians moved from camp to camp in their yearly cycle of searching for food, they carried possessions on their backs and packed them on travois pulled by domesticated dogs.

Long after the dog had joined mankind as a beast of burden and hunting companion, the horse became the second animal to be domesticated. The early development and refinement of distinct horse breeds took place around 2500 B.C. in the Near East, then in Europe and much later in America. The earliest known direct ancestor of the horse appeared in North America 40 million years ago. Fossil evidence in North America gives scientists a vivid illustration of the evolutionary process of the horse. Horses of today are large hoofed mammals, but the first horses were small animals about the size of a sheep, with several toes on each foot. Although horses became extinct in America during the Ice Age, it is believed that horses traveled westward toward Siberia along the Bering Land Bridge and survived in Europe and Asia.

The Spanish are credited with the reintroduction of the horse to North American soil. First by Christopher Columbus, and then by Spanish Conquistadores early in the 16th Century. It is easy to sit back and pick history apart by speculating that if a particular plan had not been implemented, a more ideal world would have existed. One such case evolves around the arrival of the horse in North America. One can theorize that if the reintroduction of the horse could have been used solely for the advancement of the North American people, their lives could have been very rewarding. But as European conflicts have proven, this perception would not have remained perfect forever. Be it countries or tribes, the wealthier, more powerful societies dominate the less fortunate. Therefore, until the horse was replaced by more advanced transportation, it played a major role in many conflicts of the world. And this grim fact of history would be repeated once again in North America.

In Spain, like much of Europe, the horse had already been in use for centuries. The horse was an intricate and successful part of their military accomplishments. Early Spanish explorers must have been surprised to discover that the inhabitants of the New World did not possess horses. These explorers, like their ancestors, were trained in military tactics which involved horses and were prepared to do battle with men likewise equipped. A well-mounted army against an enemy totally afoot, had a decisive advantage. The Spaniards must have felt a sense of certain victory in their quest to conquer the Indians; an assumption that would eventually prove fatal.

Stallions were brought to North America on these early expeditions and were used exclusively by the explorers. Considering the size of the Spanish sailing ships, and the length of time for a voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, bringing horses to the New World was a major achievement. In the latter part of the 17th Century, Spaniards, arriving in increasing numbers, brought horses into southwestern North America for mounts and for work horses. As colonization began and working stock – which included mares – were brought to the New World, laws were quickly established preventing Indians to own or even ride horses. The Spanish strictly adhered to a policy of not giving or trading guns or horses to the Indians. They realized how important a monopoly of these items were in order to maintain a military and a psychological superiority over the southwestern tribes. However, two flaws in this practice were soon realized. First, a great deal of straying occurred due to the Spaniards’ open range system of ranching and many of these wandering horses were not recaptured. They either became ancestors of the wild horse herds of the West or they fell into the hands of the Indians. The Spaniards second failure in holding onto their monopoly happened when they trained Indians in the occupation of tending, feeding and currying their horses. While caring for the animals, the Indians realized the advantages of owning horses and probably by example, quickly learned how to ride. Inevitably, horses were captured or stolen from the settlements and nurtured by Indians who were familiar with their care.

Spanish horses slowly began to spread over the West by intertribal trading and by raiding parties who not only stole horses from the Spaniards, but also from camps of their enemies. But the greatest single act that hastened the spread of horses to eventually every tribe of North America was the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. This massive revolt liberated untold numbers of sheep, cattle and horses to the Indians. This release spread horses like a slow flood across the continent. The Pueblo tribes had a well-established agricultural culture, and the horse offered little toward the enhancement of their development. For the Pueblos, the horse was regarded as a trade item.

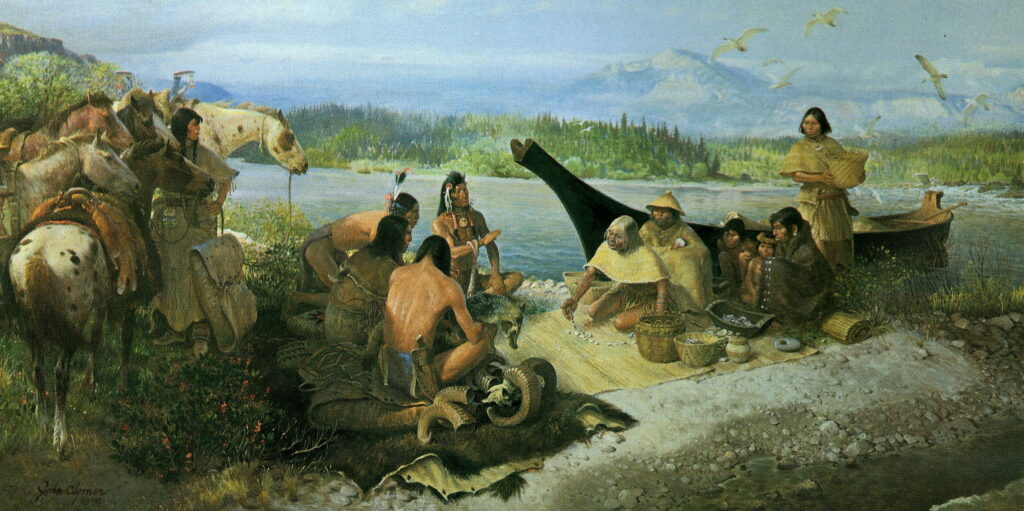

The spread of horses among the North American tribes can not be verified in any set sequence, as these people kept no written history. But for the next two centuries, the horse became a changing force for many tribes throughout North America. The trade routes that crisscrossed the country between tribes and cultures provided an unbelievable source of goods, such as pipestone, seashells and obsidian. Horses were now added to the exchanges between southern and northern tribes. Innumerable horses were traded or stolen in raids, while others broke free to roam and multiply across the plains.

Tribes viewed the horse as a large, strange animal that was strong and moved fast. For many tribes, horses were thought of as a larger version of their domesticated dog and referred to it with such names as “spirit dog.” They realized that this animal would not only pull a much larger travois of goods, it could also transport people and increase the efficiency of the hunt. Elderly tribal members, who previously had difficulty in keeping up when camps were moved, would now travel by horseback. The pace of life, that had existed for generations, had suddenly quickened.

But like all advances in society, the horse was not utilized by every tribe. One such tribe was the Mountain Shoshones, who lived high in the rugged mountains where grasses had a short growing season and travel was impossible for horses over most of the terrain. Dogs remained the beast of burden for Mountain Shoshones throughout their existence.

Tribes across the Great Plains had access to the horse around 1720. The arrival of the horse made its way into what is now Canada by 1770. The introduction of the horse spread faster on the west side of the Rocky Mountains than on the east side, due in part to the wide open plains to the east of the Rockies. The Great Plains provided a nearly endless supply of natural grasses and with this bountiful store of feed, a great number of horses could be nurtured. Thus, the need for tribes to reduce herd sizes slowed down the flow of horses northward.

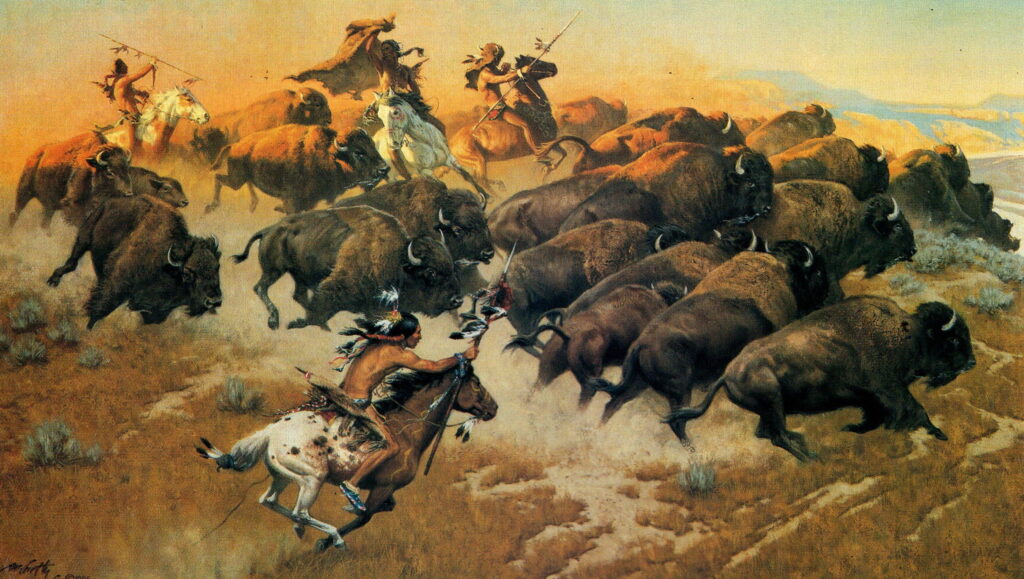

The acquisition of the horse greatly changed the life of the Plains Indians. Buffalo, which was their commissary, continually moved in search of grass to sustain them. Horses enabled the Plains Indians to become more mobile and follow huge herds into the vastness of the Great Plains – which was buffalo country. Heavier lodges, greater stores of meat, harvested berried and roots, and larger amounts of essential items could now be packed on the horse-pulled travois. Women were in charge of moving camp and owned the horses their family needed to carry their lodge and belongings. Horses used for packing were the heaviest and quietest of the herd and most likely the oldest. These docile horses could be trusted to stay calm if a mishap occurred.

From the time children were born they spent a portion of their upbringing on horses. Infants, placed in cradleboards, were strapped to their mother’s back when she rode the horse pulling the travois. Small children either rode with their mother or were seated on top of the travois during the move. Children learned to ride as soon as they were big enough to straddle a horse.

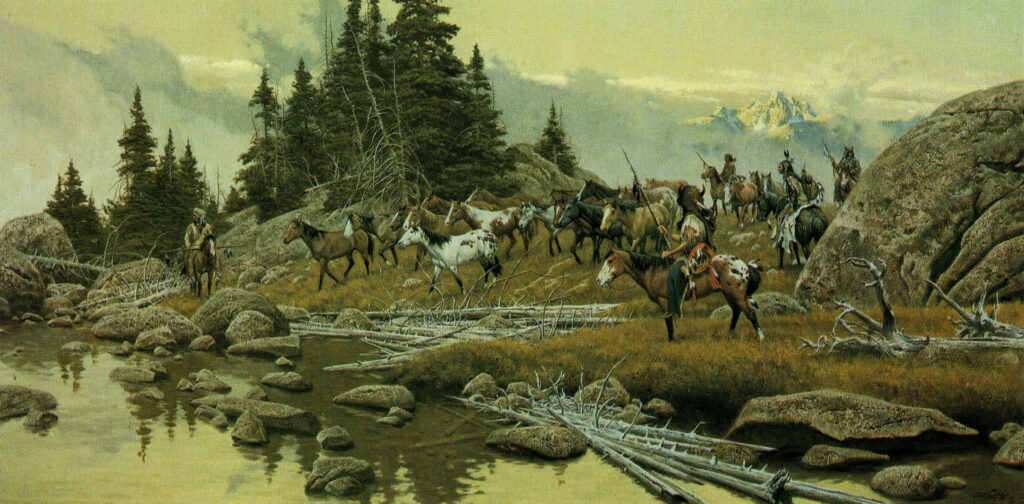

The Plains Indians became excellent equestrians and for a time they dominated the Great Plains, leading lives as accomplished horsemen, successful hunters and fearless warriors. After a battle, young warriors often received greater glory with the number of enemy horses they brought back to camp than by the number of men conquered. The Plains Indians determined wealth by the number of horses one owned. A family with several daughters were sure to increase their status. Suitors, asking for a girl’s hand in marriage, would offer her father as many horses as they could gather for a dowry. However, a tribal member could go to sleep one night the rich owner of a large horse herd and awaken the next morning to discover, that during the night, an enemy had taken all his wealth in a quiet raid.

For many tribes, horse stealing was a major part of their lives. They stole horses not only for the honor in performing cunning acts of bravery, but to obtain a greater number of horses that were trained and ready to ride. The selective development and refinement of distinct horse breeds did not meet the needs of tribes that had become nomadic hunters.

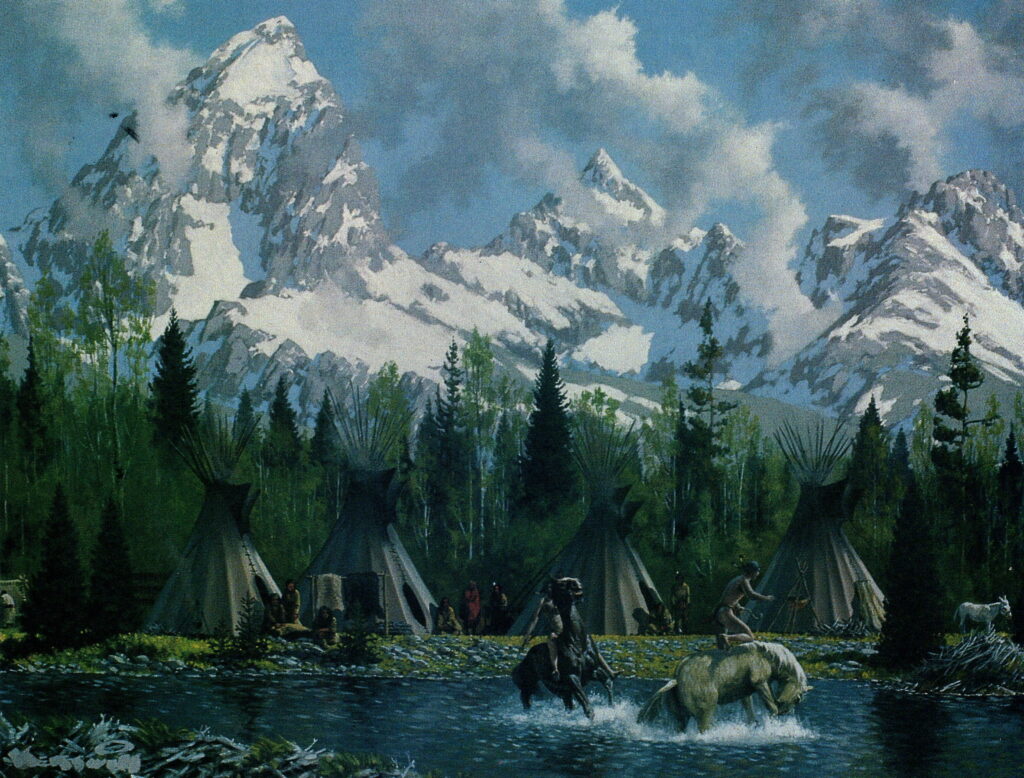

The fast and spirited horses were used for battle and for buffalo runners; secondary horses were used for day-to-day tasks. A warrior’s horse was his most prized possession. At night, it was staked by his teepee to be readily accessible at the moment of a surprise attack. Hunting buffalo took strength, skill and courage, both on the part of the horse and the rider. The horse had to have speed, endurance and the courage to run with a stampeded herd. The horse had to stay close enough to the buffalo to enable the rider to down the huge animal. The rider, using his hands to position the bow and arrow or spear, had to convey instructions to the horse with knee and foot pressure while traveling at full speed amidst the dust, noise and confusion of the stampede.

This golden era of the mounted Plains Indians and their Buffalo Culture lasted a comparatively brief time; barely a century. Early trappers, who had entered their land to harvest furs, were not seen as a threat to the tribes. But by 1840, white immigrants were entering into their territory and would continue to disrupt their lives for decades to come. By the 1860s, the Plains Indians were forced to move away from their traditional hunting grounds. The Great Plains were now divided by wagon roads, railroads and telegraph lines. The white man, who had introduced them to the wondrous horse, was now breaking treaties and taking their homeland. Numerous battles were fought between the tribes and the United States Government. Officially, it is recognized that the end of the Indian resistance came in 1890 at Wounded Knee.

The acquisition of the horse spread at a faster rate west of the Rocky Mountains. The horse moved from the Navaho and Apache to the Utes and the Shoshones to the Nez Perce, Cayuse and eventually to the Blackfeet. There were a couple of reasons for the faster progression. First, their territory did not provide the same abundance of grass, therefore more horse trading occurred among the tribes. Secondly, tribes living in this region were not as nomadic as the Plains Indians. The culture of the tribes of the southwest were agricultural and the northwest tribes were fishermen. Many of these tribes acquired the horse, but did not have their entire lifestyles changed.

It seems somewhat interesting that a tribe from this region would become noted for horse breeding. It is believed that the Nez Perce Indians acquired the horse as early as 1710. Surrounding tribes envied and prized the spotted horse of the Nez Perce long before the white man arrived in this region. One of the earliest known accounts of the white man’s recognition of the spotted horse came in the journals of Lewis and Clark. Meriwether Lewis, himself a horseman from Virginia, entered in his journal of Feb 15, 1806, a description and his impression of these horses:

“Their horses appear to be of an excellent race; they are lofty, elegantly formed, active and durable…Some of those horses are sided with large spots of white irregularly scattered and intermixed with the black, brown, beige or some other dark color.”

The Nez Perce territory, where the states of Washington, Oregon and Idaho meet today, was ideal for raising horses. The Nez Perce Indians needed a controlled environment for their selective breeding. The lower valleys provided abundant winter range, while the higher plateaus supplied good summer pasture. Their annual moves from fishing to hunting and harvesting grounds kept their horses in good feed year round. Rugged mountains in this area offered a deterrent to enemy raids.

It is unknown how and why the spotted horse was chosen. Most likely the unique coat pattern was a factor as well as their strength to endure the mountains. Only the best animals were allowed to produce offspring, the less desirable were traded off. The Nez Perce delighted in showing off the qualities of the spotted horse in races and other competitions. Hunting parties eventually crossed the mountains into buffalo country. The Nez Perce took herds of horses with them for trading, which increased the spotted horse population on the east side of the Rockies. To the west of their homeland, the Nez Perce rode their spotted horses to trade with the coastal tribes and returned with trade goods that enhanced the lives of their people.

The country of the Nez Perce was no exception to the wave of immigrants and they were forced to give up most of their land. In 1877, the Nez Perce protested and U.S. Army troops were ordered to remove Chief Joseph’s band to a small reservation. In desperation, the chiefs led their people on a brilliant 1700 mile retreat to Canada. The endurance of the Nez Perce, the strategy of the warriors, and the quality of the horses they had bred, gained the respect of the military men who stopped them just a days ride from the Canadian border. After the Nez Perce surrendered, their horses became the spoils of war which broke up their herd.

Today, tribes throughout the country utilize horses in their ranching activities, on hunting trips, for pleasure riding, in horse shows and for rodeo stock. Like their ancestors, they enjoy the advantages of owning horses.

The Appaloosa

The name for these spotted horses evolved in the late 1800s. Early settlers called them “a palouse horse.” The name came from Palouse Creek that flowed through the country in which these horses were found. From there it evolved to “Apaloosey” and eventually became “Appaloosa.” Many of todays Appaloosa breeders are members of various Indian tribes who share the pride of the Nez Perce in raising this magnificent animal.

A vast majority of foals are born at night. Although the horse is a domesticated animal, natural instincts of nature prevail. Under the security of nightfall herds are quiet and predators are less likely to see or scent a newborn at its moment of total helplessness. From the time a mare lies down, until the foal is standing can take only 20 to 30 minutes. Bonding between mare and foal begins at once as the mare licks and encourages her newborn to get up. Once up, which may take several tries, it instinctively knows to nurse and quickly searches out the location. Within days it can keep up with its mother and the rest of the herd. The foal can run amazingly fast at the slightest strange sound or sudden movement. As gentle as a mare might normally be, she becomes very aggressive to anything that could harm her foal.

Horse of Many Colors

Warriors often paint their horses, but this breed provided its own painted markings. These markings also furnish a type of camouflage, especially in the trees or brush, by breaking up the outline of the horse.

The rump of this six month old foal is not uncommon for the Appaloosa. As winter approaches and the coat begins to thickens, the spots can often rise above the base coat of white hairs. This breed of many colors can have an array of shades and patterns, spots within spots, unique patterns or a solid base. A rider of any culture is proud to ride on a colorful, flashy mount.

Horse of Changing Color

A color and/or coat pattern an Appaloosa is born with can change. They may transform slowly over the first three to five years, or during that same time period they may shed their winter coat one early spring and be nearly unrecognizable. Some horses will not change a significant amount from the day they are born, but once the color or pattern changes, it never reverts back.

The color or pattern can not be predetermined from the parents. It is always a surprise when a newborn arrives. Foals, even though born of the same parents often have entirely different coat patterns and colors. Some mares will throw a wildly patterned foal one year and the next year have a foal of solid color; both from the same father. There are also mares who show no coat pattern and consistently have foals with a wide range of color and spot variations.

This unique quality of the Appaloosa must have amazed the Nez Perce as they developed their breeding program. The Appaloosa, which have always been held in high esteem by the Nez Perce, are also the pride of both Indian and non-Indian breeders today.

St. Stephens Indian Mission Foundation is a non-profit organization, incorporated under the laws of the State of Wyoming on March 31, 1974, and listed on page 184 of the 1993 OFFICIAL CATHOLIC DIRECTORY. The sole purpose of the foundation is “to extend financial support to St. Stephens Indian Mission and its various religious, charitable and educational programs and other services conducted primarily for the benefit of the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone Tribes on the Wind River Indian Reservation.”

Posted in Notes From the Field