May 23, 2017

Over 200 years ago, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark embarked on “a monumental epic in the history of the U.S.,” as described by Fort Washakie sculptor R.V. Greeves.

In the other direction on America’s timeline, Greeves thinks he’d be able to complete every artistic idea in his head about 300 years from now.

In the near middle of this history—where we are today—Greeves is in the throes of producing art that complements the journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Greeves explains that in the centuries since Lewis and Clark returned from the Corps of Discovery venture across the burgeoning nation, scientists and historians have been doing the same, and act called editing.

“What I’m doing is editing the journals with sculptural work, which has never been done before,” Greeves explains.

“What I’m doing is editing the journals with sculptural work, which has never been done before,” Greeves explains.

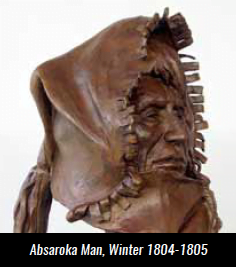

The focus of this project—his primary focus in the studio—is the Native American Indians encountered by the Corps of Discovery, most of whom had never witnessed a white person prior to the years of this expedition.

“That was the purest time to ever see the American Indian,” Greeves reflects.

His “In the Footsteps of Lewis and Clark” collection, now up to more than 50 bronzes, represents those moments and interactions. Through historical research, Greeves is learning and sculpting each of the tribes the expedition encountered, from the plains to the Coast.

“They basically touched all groups of people in this country [at that time] except the southwest Indians, of course,” Greeves explains.

Many of his Native subjects weren’t just witnessed. They assisted the researchers on their mission. The people Greeves sculpts were instrumental in the success of the expedition. Lewis and Clark and their team found themselves in challenging situations numerous times across what would become the United States, and it was often Natives who helped them persevere.

“The Indians played a bigger part in it than history has given them the credit for. Without them, the expedition would have failed,” Greeves declared.

A key element of the success of the expedition was the collection of information, as mandated by President Thomas Jefferson. The scientific mission was designed to collect extensive data from the across the continent and return it to Jefferson. The team returned with may materials and journals, of course, but Clark and others have spent lifetimes analyzing the field notes.

“It was such a monumental undertaking there becomes no end to the project,” Greeves explains.

Now a part of that undertaking for several decades, Fort Washakie’s resident sculptor, himself raised in Missouri, has every intention of upholding the tradition of dedicating one’s life work to Lewis and Clark’s charge.

Now a part of that undertaking for several decades, Fort Washakie’s resident sculptor, himself raised in Missouri, has every intention of upholding the tradition of dedicating one’s life work to Lewis and Clark’s charge.

“I’m going to work on it until I die,” he declared in response to the question of how many pieces his “In the Footsteps” collection will ultimately include.

Many of Greeve’s pieces can be found in museums and exhibits across the very continent he continues to help Lewis and Clark describe. Many reside in his gallery in Fort Washakie, which is open by appointment. Greeves has sculpted extensively beyond his edits of Lewis and Clark’s journals, almost exclusively of Native American subjects.

“I’ve only lived among Indians my whole life. I don’t know anything different,” he offers. Born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri, he moved to Fort Washakie on the Wind River Indian Reservation as a young man. He has been creating art from the heart of the Reservation for about 60 years now.

Though he hasn’t found a way to extend his time in Fort Washakie by another 300 years, Greeves has found a way to extend the understanding and presence of the people who called these mountains home well before he was born.

Posted in Notes From the Field