July 6, 2018

Small towns are often recognized for community unity and neighbors looking after each other. They also tend to have their cliques, in the way that high schools always have. It can be—if you’ll pardon the on-the-nose metaphor—a double-edged sword.

These characteristics expressed in the bladesmith community of Wind River Country/Fremont County are representative of the qualities of small towns. The truth is beautiful and raw: We hold each other up, but that doesn’t mean we all always get along.

As far as I can tell, the surprisingly extensive community of bladesmiths in Wind River Country’s small towns started with another trait that runs strong in Wyoming: industrial self-starting.

Ed Fowler didn’t want to live in Wyoming, and he didn’t want to ranch. But he came back to help his family. After a few winters, he was still living outside of Riverton, having fallen in love with the horses, the cattle, the personal space, and the freedom.

“I started making knives. In the wintertime there isn’t much else to do. I can’t stand television. Haven’t watched television since Ronnie Reagan quit… So just started reading, started making knives,” he said, as matter-of-factly as he declares anything else Ed chooses to talk about.

Over countless iterations—fueled by his intellectual curiosity, practical knowledge of ranching, and high expectations—Ed developed a very specific knife with a workhorse of a blade. In fact, he has made his mark on the practice by developing particularly resilient steel. His “no secrets” philosophy translates to a free master class in his discoveries, collaborations, and lab research that made him famous—or infamous—in the bladesmithing world. Spend a few hours with him like I did, and you’ll walk away familiar with terms like “multiple quench,” “52100 steel,” and “metallurgy,” as well as a certain intrigue you never had with knives before.

Ed’s steel isn’t the only part of his knives born of his ingenuity. He makes one particular style of handle on his fixed-blade knives, and it’s for reason: experience.

“This is the safest knife that you can use,” he said, as he pushed the tip up against the edge of his kitchen table. “See how it turned? It doesn’t bite me. I cannot think of any way to make that knife safer.”

Beyond the new techniques in steel selection, bladesmithing, and handle design, Ed brought an evolution to Wind River Country.

Audra Draper first started working for Ed as a ranch hand.

“I went out to the shop one day and the forge was running and I thought, ‘Oooh I want to play in the fire! I want to make knives, too!” she recalled. She continued: “He said, ‘ah, girls can’t make knives.’ So that was pretty much the beginning of that story because then, regardless of anything else I did in my life, I had to prove girls could make knives.”

Ed had told me a similar story earlier, but in his version, he said that to goad Audra into giving knifemaking a try.

The beginning of the story, however the conversation went, leads to Audra Draper becoming the world’s first female master bladesmith.

Though Audra and Ed eventually parted ways, they speak of one another with respect. Fondness is in the memories they tell, but there is distance in their language. They still share a commitment to excellence in craftsmanship, fueled by passion for knifemaking. And their stories are inter-woven in the fabric of Wind River Country because they are both teachers at heart. The list of local knifemakers is surprisingly long in this small community.

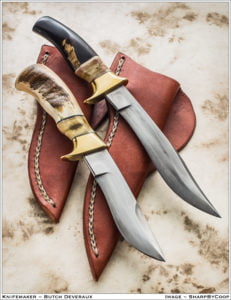

One of Ed’s newer disciples, Butch Deveraux, has a self-imposed allegiance to what Ed taught him. Butch explained that after listening to Ed expound upon his quest for the safest, toughest, sharpest knife, he got sucked in. And he loves that knife.

“I kind of pledged myself to Ed. I asked him if he minded if I followed what he was doing,” Butch explained. “I basically vowed to Ed that I would help to continue to strive to make knives better… I still go down and work with Ed. I work in his shop with him, forging and just of course the friendship.”

He does allow himself a few touches of Butch Deveraux artistic license. They are his knives, after all.

“I have him look my blades over, he always gives me constructive criticism,” Butch added.

Butch isn’t only keeping life in the Fowler knives line. He also supports a cause close to his heart through the craft. A number of veterans have found the practice of knife making and bladesmithing to be healing. Butch donates to the Special Operations Warrior Foundation, for instance by raffling off one of his knives.

Audra and her husband and fellow knifemaker, Mike, also believe in the power of turning a hunk of metal into something beautiful, tangible, and utilitarian. As much as they enjoy it themselves, both are committed to find ways to best impart that knowledge, focus, and love on students, including military veterans. The Drapers are in the process of expanding their shop to accommodate more frequent and larger classes than the four-day courses they currently offer every couple of months. Part of that plan is making the workspace more inclusive to people in wheelchairs or managing PTSD.

Students typically stay with Mike and Audra and work long days. They conclude the intensive class with a knife they have fashioned from start to finish under the careful and gregarious guidance of Audra and Mike, gregarious applying more to Audra than Mike.

“Audra loves people and she’s a good instructor,” Mike said. “I tolerate people and I melt down really quick. We’ve got this little phrase: I keep the wheels on the bus. She’ll sit in here and visit with people in the morning and have coffee and breakfast and I’ll sneak out to the shop and I’ll have the forge out and the propane going and the steel going and everything ready to go and she just walks out there and boom the steel’s hot.”

“Boom everything’s ready to go!” Audra says at the same time. “But he likes that. That’s where he’s comfortable.”

“I keep the wheels on the bus,” Mike said. “Her techniques and her styles of the knives that she builds is so different than mine if I try to get in there to help with instruction—”

“We do things different.”

“If I start to show [students how] to grind a blade a certain way she’ll come in and say, ‘we don’t do it that way.’”

“We are working on that,” Audra laughed.

“We are working on that a little bit,” Mike echoed.

The two complement one another’s styles in the same ways their knives do. Audra’s blades and handles are breathtaking. The Damascus style metal comes to life with patterns flowing through the blade. She constructs her handles from materials like local antelope horn, nickel silver, and ivory. Her signature design flair is leaves, and she likes to throw in opposing, rather than matching, angles.

Mike, on the other hand, builds more utilitarian—but no less beautiful—folding knives. His machinist background is evidenced by the precision of their parts and their action. The materials are a bit more understated, but their shine highlights the care he takes with their appearance and with their movement.

Though they have self-imposed his-and-hers sides of the workshop, Mike and Audra speak about one-another’s products with glowing admiration.

The two also eagerly rattle off a list of local bladesmiths they recommend talking to, but the list runs too long to include everyone in one blog post. So as the Wind River Country knifemaking community grows and changes thanks to people like Ed, Audra, Butch, and Mike, it remains a small town of connected artists, and they remain dedicated to holding one another up.

Posted in Notes From the Field