August 13, 2019

By Lois Wingerson

You don’t need to spend long in Dubois before you begin to appreciate the importance of the visual fine arts to this tiny village at the edge of the Wyoming wilderness. Galleries and art shows are prominent, and artists and photographers come for annual workshops.

It’s natural to credit this to the spectacular landscape, but Dubois is hardly the only small town that is set beside post-card vistas. It takes longer to trace this legacy to its roots, to the influence of one pair of settlers who came here nearly a century ago: a cowboy who was a sculptor and his wife, who was a painter, an art teacher, and so much more.

Mary Cooper Back was not a Wyoming native, but she was one of many young women drawn here inexorably by falling in love with a cowboy. Dubois remembers her most fondly as an artist, but at various points in her life she was nearly everything that bespeaks Wyoming: homesteader, dude rancher, naturalist and wildlife biologist, taxidermist, carpenter, dude ranch owner, pack-trip outfitter, and avid hiker. She was also an amateur philosopher, a lay minister, and even a certified aircraft mechanic.

Born in Minneapolis in 1906 and raised in Vermont, Mary met her future husband Joe Back, a cowhand from Dubois who loved to sketch, at the Art Institute of Chicago. Joe had come to the Art Institute with the help of an artist who met him at a dude ranch.

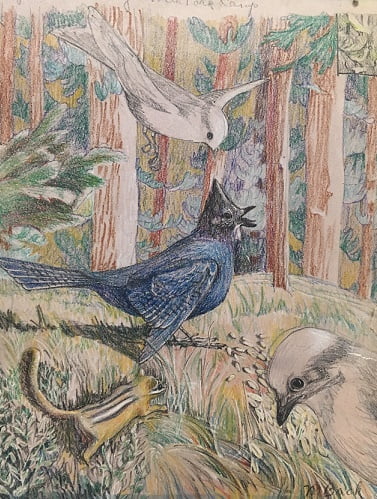

Mary had also been a habitual sketcher in childhood, and in college she had a job as an illustrator for the biology department. Art and wildlife were her two passions ever after. Her parents moved to Chicago while she was in college, and afterwards she worked as a taxidermist at the Academy of Sciences and as an intern at the Field Museum of Natural History, where she took a class on the structure of animal bones and muscles.

Joe and Mary shared a crazy dream: Move to Wyoming and make a living from their art. They married in 1933, and remained in Chicago for a while. Mary worked as curator of the new Trailside Museum in River Forest, which was a refuge for injured animals. When animals died, she sketched them and then preserved their remains with taxidermy.

In 1935, the couple kitted out an old Buick as a homemade camper and set off for Dubois, with the goal of buying a ranch. When a friend offered to invest half the cost, they purchased Lava Creek Ranch, which was located west of Dubois and near the Continental Divide on Togwotee Pass. Back then there was no smooth paved highway across the Pass, and no snowplowed route to town in the winter. Nor was there indoor plumbing at the ranch, or electric lights, or phone, or mail delivery, or even furniture.

Joe set up a stove that he found in the woods to provide heat. Mary made a sofa from the front seats of an old Chevy that Joe had bought to use the motor for his saws. She made pillows from sugar sacks and elk hair she found outdoors, and kitchen cabinets from wood boxes. She built straight-backed chairs by hand. They got by. It was an adventure.

At first, their love of doing art gave way to mere survival. They decided to build more cabins and open a dude ranch. It had its first season in 1937, promoted by a brochure that Mary created.

“This is not a hotel, but a frontier ranch, still being carved out of the wilderness,” it reads. “We raise our vegetables in fresh-turned virgin sod. We are building our meadows from sage benches and willow flats. We saw our own lumber from pine logs cut on the Home Ridge.“

Joe sold a little art in Yellowstone Park, but mostly it was the dude ranch that occupied their time and supported their needs. In 1940, they opened a different dude ranch much closer to town. Mary herself built a new wing onto the main house to serve as a bedroom. She also took a job as the town librarian, curating “2200 books in an ancient log shack,” as she put it.

Like much of dude ranching, their venture began to fail with the onset of World War II. Joe took a welding course and got a job in California building ships. Mary later joined him there. She got a job as an entry-level mechanic for United Airlines and in due course was certified. We are told that she found the mechanics’ course fascinating.

Returning to Dubois by 1945, Joe and Mary began to achieve their dream of living purely from their art. With the sales of their paintings and drawings, as well as Joe’s sculptures, they could just get by.

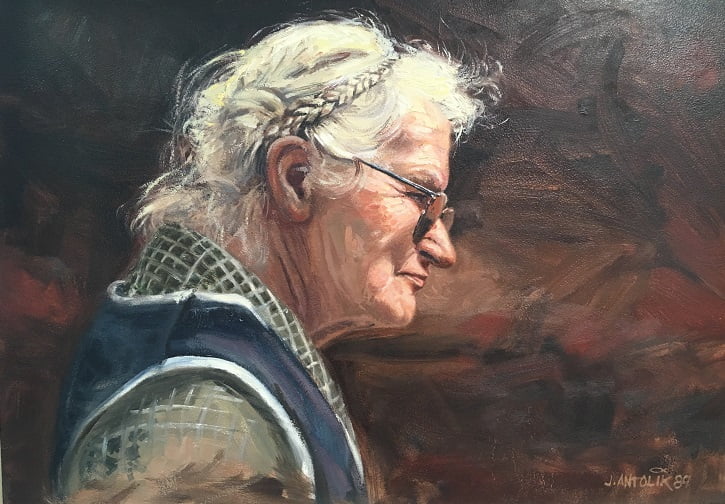

Tourists were particularly fond of Joe’s small animal models, especially the little pack horses. Mary became the technologist who mastered the production process, as well as the assembly-line worker. But her own drawings and paintings were also attracting attention.

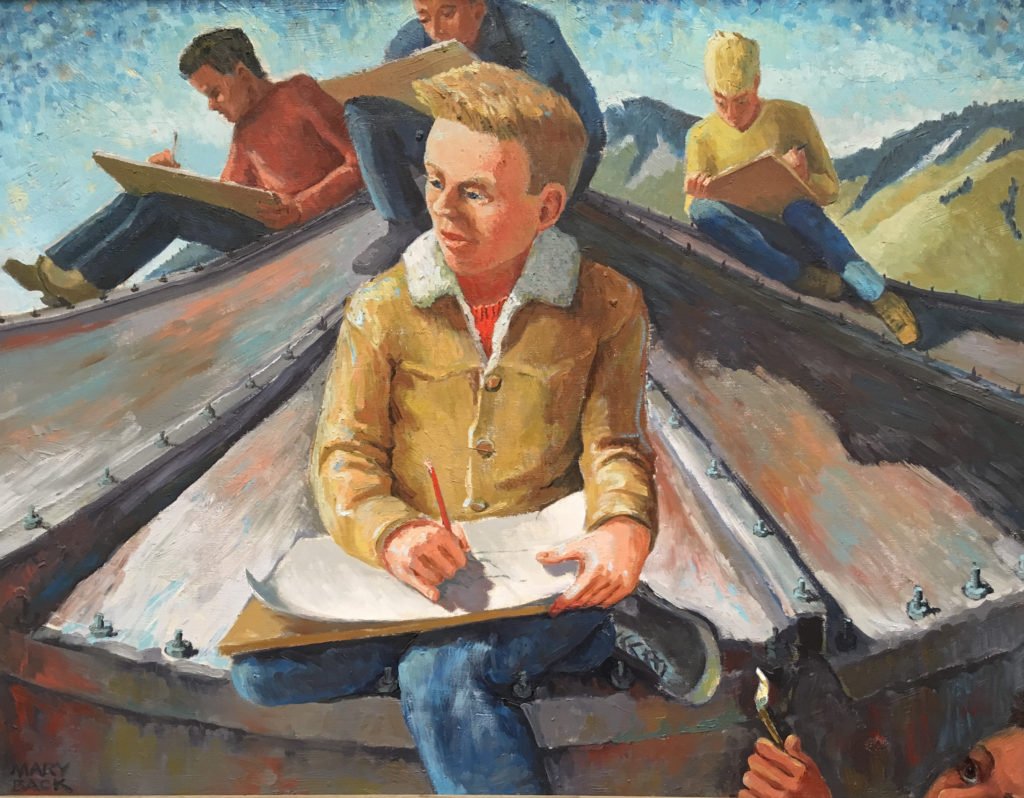

The University of Wyoming asked her to teach an extension class in painting, and 10 women quickly signed up. By the end of 1949, she had 65 students and was teaching in Lander and Riverton as well as Dubois, after turning their car into a traveling art wagon. The commute kept her away from home and the assembly line, but it also spread her renown.

From the outset of the art course, Mary established an exhibition in Dubois featuring the works of all her students. She considered all of the artwork good, Twila Blakeman recalls, because each of the students gave of herself or himself and had something of value to offer. Eventually the exhibitions evolved into the Wind River Valley Artists Guild, founded by Mary and some of her students in 1954, and still a vital force in the Dubois community.

Mary didn’t merely teach art; she used her art to teach. Some Dubois families have a prized keepsake from Mary Back: One of the drawings from her beloved “Chalk Talks” during Sunday School or worship at St. Thomas Episcopal Church. Mary would illustrate a Bible lesson with an image chalked on the spot, and afterwards give the drawing to a lucky listener.

She would end each Chalk Talk by filling in the black around the images; only after adding the darkness does the image come clear, she would explain. How many heard the unspoken personal metaphor, knowing that her own brightness was forever shadowed by the loss of her infant daughter, who had been strangled at birth by the umbilical cord?

It took Mary many years to emerge from that depression, helped by the church and its priests, Coach Wilson and Burdette Stampley. For whatever reason, Mary and Joe never had other children.

It is tempting to speculate that the death of infant Martha ultimately nurtured Mary’s deep reverence for wildlife and her growing conviction that all life is one, and therefore death is not a finality. “Thinking of all life as coequal with equal right upon this earth … it is sad and humbling to consider the carnage necessary … to keep us alive,” she wrote once “Much as I enjoy elk meat, I am often impressed strongly with that point of view when on a hunting trip.”

Mary came to believe that Jesus Christ was not the only creature to say the words “This is my body broken for you . Take. Eat.” She sensed the same blessing coming from a deer as its life ebbed during a hunt, and she treasured the lives of all living creatures as part of an endless web of birth, death, and renewal throughout the earth.

“We are part of all life,” she wrote, “and all life is part of us. We have a right to share the excitement of a birch tree when the new sap comes running up its stems, and a right to feel flattered when the bald eagle hovers low above us looking us over with fierce yellow eyes, considering us as one equal to each other.”

She was especially fond of birds, and knew a great deal about them. This is most apparent in her 1985 book Seven Half Miles from Home: Notes of a Wind River Naturalist, the memoir of her daily morning walks inspired by a doctor who recommended that she walk a mile before breakfast each day, for her health.

In the book drawn from her journals, Mary described in vivid detail the natural world that she saw as she hiked: the birds, the four-footed mammals and beavers, but also the plants, the weather, and the deep history of the forces that created the spectacular landscape of the Wind River Valley.

“The whole land pulsates, “ she wrote, “like deep breaths drawn over hundreds of years. During periods of uplift the rejuvenated river cuts fast. During sometimes long periods of subsidence the river spreads lazily out into lakes and sloughs … Part of Wind River’s present project is the sculpturing of the Badlands. Its tributaries, partnered with storms and wind, have cut the soft striped rocks into intricate forms and patterns.”

Mary remained fairly healthy and quite active for most of her life. At the age of 69, she had joined younger friends for a trek all the way across the rugged Absaroka peaks from the Dunoir Valley west of Dubois to Cody. She called it “some of the highest, wildest, and cliffiest country in the Rockies.”

Unfortunately Joe suffered from crippling arthritis and digestive complaints for much of his later life, and he died of bladder cancer in 1986. With her lifelong companion and working partner gone (“like an amputation,” she said), Mary became more active in public life. On the day after his memorial service, she led a group of college students on an Audubon hike.

She continued to paint, but she also finished the last of Joe’s many books about the West. She completed a course for lay ministers, became an activist in favor of wildlife conservation, and guided wilderness treks for the Dubois Museum.

After surviving a few strokes, Mary Back passed away on May 28, 1991 at the age of 85. After her death, neighbors worked together to empty Mary’s freezer. They found the remains of countless birds, preserved so she could study their form and do them justice in her artwork.

“Mary’s gentle persistence left a flourishing art guild and a vital community library,” writes her niece Ruth Mary Lamb in her biography, Mary’s Way. “Stop at any store in town,” she adds, “and someone will probably have a story.”

Retired Dubois Mayor Twila Blakeman recalls that Mary was a “loving, giving person” who never had a cross word or criticism, and saw beauty in everything and everyone. Piano teacher and former art student Helen Sabatka says simply, “She was one of a kind.”

People remember Mary as plain-spoken, strong, and serious-minded, an interesting contrast to Joe, who had a cowboy’s way of talking with a jokester’s turn of phrase. Those invited to dinner recall the simplicity of the meal and the straightforward good nature of their hospitality.

Mary’s personal style was carefree and oblivious to the fashion of the day. After her clothes were smoke-damaged in a house fire late in her life, a friend drove her to Riverton to buy a new wardrobe. Mary carefully put it away, washed the old clothes, and continued to wear them.

“… we too are gathered in her light,” said her friend Lyndie Duff in a poem at her memorial service, “and brought to see and feel, by osmosis, her great gift for life.”