March 14, 2017

By Casey Adams

Every piece of Tom Lucas’ artwork has lived several lifetimes.

A piece’s first life is that lived by Tom, by his friends and family, conjured up from the well of rich stories he has compiled over decades of life on Wyoming and Montana ranches, the Wind River Indian Reservation, and in Dubois.

“My whole life has revolved around Native American and cowboy culture and ranching and hunting … I’ve been cold and hungry and wet and half froze to death, and those things come out when you’re doing your artwork,” Tom said. “To me it is so important that you reach back down into yourself and pull out all those feelings, those experiences.”

“My whole life has revolved around Native American and cowboy culture and ranching and hunting … I’ve been cold and hungry and wet and half froze to death, and those things come out when you’re doing your artwork,” Tom said. “To me it is so important that you reach back down into yourself and pull out all those feelings, those experiences.”

Whether it’s a bear sculpted from stone, a beaded moccasin, a Native American-style war bonnet, flint knapping, or one of the bighorn sheep bows for which he is famous, Tom has a personal backstory behind each item.

A piece’s second life is taking and holding physical form.

For example, in his late 20s, Tom’s interest was piqued by a literary depiction of bows that the Mountain Shoshone or Sheep Eaters of Wind River Country once used, crafted from the horns the area’s bighorn sheep had shed. After searching the library and seeking out guidance on the process, Tom was left without answers. As he tells Susan Carse Norris in her biography “Tom Lucas: Western Artist,” Tom’s interest in the bows—and the process of creating them—didn’t waver.

“The ultimate challenge is to make one,” he decided, according to the biography. Knowing only that that sheds were soaked in hot water for a day or two before being manipulated into a bow shape, he began his work.

“It’s kind of hard to explain,” Tom told us, “but for me I have to be able to see [a piece of art or craftword] in my head. I have to be able to visualize it really explicitly.” And when he does, he can bring the picture to life in three to a dozen attempts, he estimates.

And in this case, through trial and error, experience as an artist and craftsman, and a bit of intuition, he brought history to life on the first horn. That initial bow has lived a celebrated life, even circling back to visit Tom in his shop 40 years later.

In the subsequent decades since that first bow was brought to life, Tom has completed another 40 bows and been routinely recognized for his rescue of this nearly lost art.

This cowboy artist has continued to hone his skills and develop new artistries. In fact, at the time of this interview, Tom was working hard on another demanding undertaking: a little jewelry box inlayed with pieces of sheep horn—scraps from earlier creations. Fittingly, his intended future for this carpentry piece was donating it to the National Bighorn Sheep Interpretive Center in Dubois for a fundraiser.

“The sheep horn box is probably one of the most challenging I have ever taken on,” Tom noted. “I’d actually like, when I get this one totally completed, to try that one again and see what I can come up with.”

On top of that, he’s identified a “down-the-road project” in carving a buffalo out of stone.

“I’m not a sculptor, per se, but when I get in the mood to do something … I do like to take on a new challenge,” Tom explained, a trait that becomes apparent as he describes his many endeavors, artistic and otherwise.

Buffalo are a favorite subject for Tom, and through personal and artistic experience, he has developed a strong, familiar understanding of the creatures, to which he can add an emotional component.

“If I can pull it off and make it look like I see it in my mind, that would be pretty exciting,” Tom said of his eventual miniature buffalo sculpture.

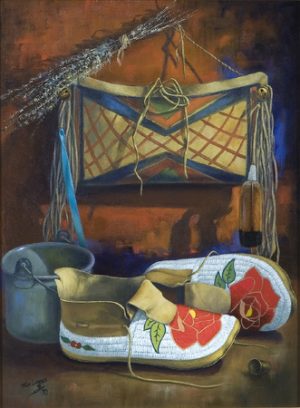

A piece’s third life is often in the form of a painting by Tom’s hand.

“I do make a lot of my props and at various times they end up in my paintings, usually several times,” Tom said.

“I do make a lot of my props and at various times they end up in my paintings, usually several times,” Tom said.

Take, for example that next challenge Tom is already mulling.

“If I can make that little buffalo carving the way I want it, it’s quite likely it will end up in my paintings at least once.”

Just as Tom’s physical pieces are grounded in reality, in emotion and a sense of place, so, too, do his paintings. They hold a share of the life Tom has lived in Wind River Country.

“When I set up a still-life, I’m trying to go back in that particular time period and I’m thinking about all the implications and all the things that are resonating from whatever I’m trying to say. You create from the heart.”

“When I set up a still-life, I’m trying to go back in that particular time period and I’m thinking about all the implications and all the things that are resonating from whatever I’m trying to say. You create from the heart.”

Tom has lived in Wyoming’s Wind River Country/Fremont County since the late 1950s, and the diversity of scenery continues to be a key element of his inspiration. An eloquent, composed man, Tom begins to ramble a bit when describing what he loves about his home.

“This area has a lot of diversity, i.e. the mountains, the desert, the badlands, you just have all kinds of beautiful scenery—inspirational scenery. And of course the people—I like the small-town atmosphere, and I’ve always liked the lifestyle that I’ve lived which is, of course, ranching and training horses and working stock … I carpenter, then there’s my artwork,” Tom explained, concluding beautifully:

“The area in general just provides a lot of inspiration for all of these venues that I work on. There’s a great deal of living here in my artwork.”

There is, indeed, a great deal of living in Tom’s artwork. Perhaps in one of these piece’s fourth lifetime, it will be visited by you in his shop in Dubois while you’re in Wind River Country.

Posted in Notes From the Field