March 13, 2023

This story was originally published by St. Stephens Indian Mission Foundation in VOL. XXV JUL/AUG/SEPT 1995 NO. 3. St. Stephens Indian Mission Foundation owns the copyright, and the story is reprinted here with permission from the Foundation. More information on the Foundation can be found following the story or by clicking on the link above.

A woman’s place in Plains Indian culture was an indispensable part of tribal life. The man and the woman were partners; he had his responsibilities and she had hers, and both were necessary for their survival. The lifestyle of buffalo-hunting tribes on the Great Plains revolved around the dangerous male pursuits of warfare and hunting. The role of Plains Indian women was to support the hunters and warriors; a task that involved considerable labor. The life of the Indian woman was indeed hard, but her value to the tribe was duly recognized. The woman’s numerous tasks promoted tribal welfare.

Daily Life and Responsibilities of Plains Indian Women

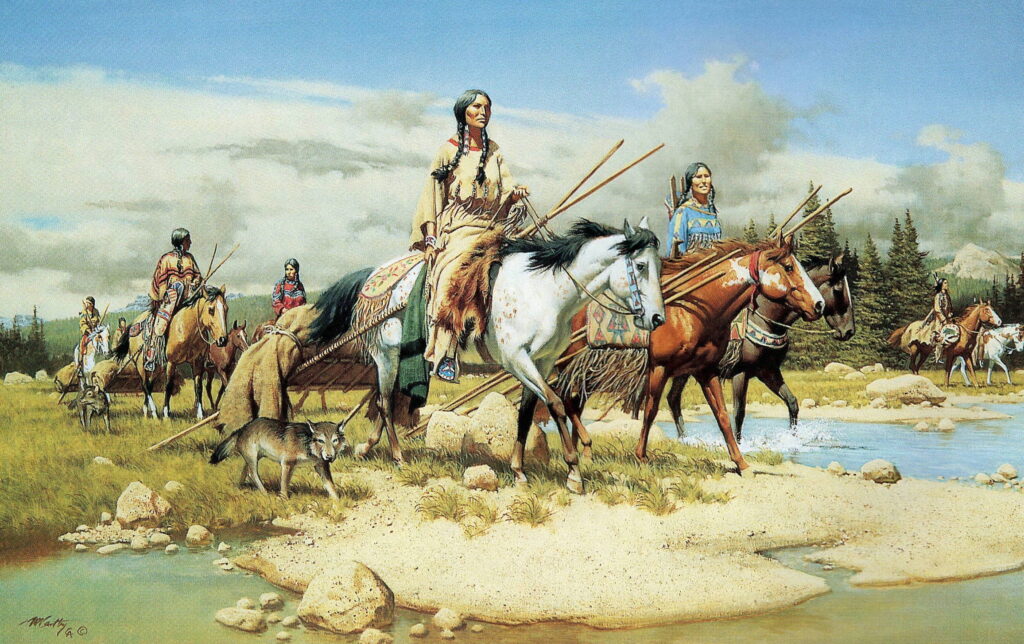

The Plains Indians lived with constant exposure to the elements, to hunger, and attacks by enemy tribes. When these nomadic peoples moved their campsite, the men rode on the outside or ahead of the group, ready to defend their families against any threat of attack and to look for game along the way. The women took down the tipi and packed their possessions on the horses and travois; small children rode with their mothers in a cradleboard or sometimes the cradleboards were tied firmly to the travois, older children often rode their horses. (Before the acquisition of the horse, the women packed their belongings on the backs of dogs or dog-drawn travois.) And it was the women who unpacked and pitched the tipi and set up housekeeping at the next campsite. Apart from being a wife and mother, this strenuous work was done in addition to their daily homemaking duties of gathering firewood, cooking food, fetching water, and making and repairing clothes, moccasins, tipis, and manufacturing household items.

(c)1988 The Greenwhich Workshop, Inc.

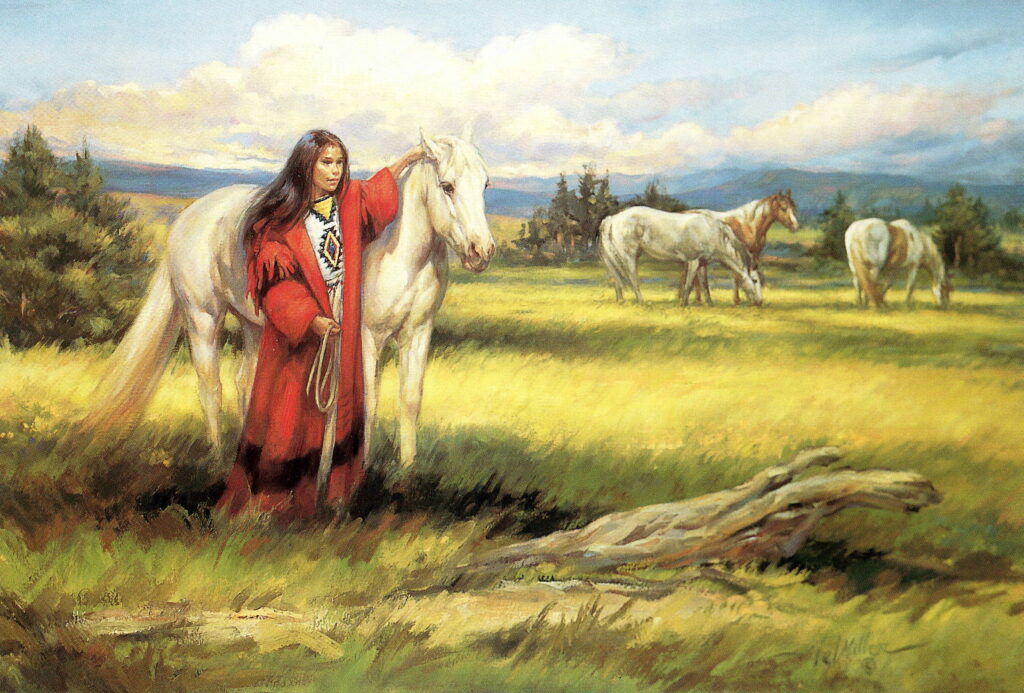

(c)1992 The Greenwhich Workshop, Inc.

Property, Independence, and Social Standing

Although early Plains Indian women had no voice in tribal affairs, they ran the home and had certain rights. For one thing, the women decided where their tipi was to be pitched in the camp circle, and for another, they virtually owned all of its contents, as well as the horses they packed when camp was moved. According to historical accounts, if a woman had a grievance, she was likely to speak up and stand her ground.

Food Processing and the Buffalo Harvest

The primary task of early Plains women revolved around providing food for their families. The harvesting of buffalo was the responsibility of the man, but once the game was harvested, it became the property of the woman. The women of the encampment often followed the men on a buffalo hunt. They waited by their travois until the harvesting was finished, and then they would rush down to start skinning and cutting up the meat. Each carcass had to be quickly attended to in order to prevent spoilage, especially during the summer months. The women, skilled in cutting the buffalo hide away from the meat, were careful not to damage the hide in the process. Before the hides cooled and became too stiff, the women quickly scraped the buffalo hides clean of fat and tissue. They scraped the meat in the fresh buffalo hides and took it back to camp on their travois. The men might help with the heaviest work, such as turning the animal over, but processing the meat and tanning the hides were primarily the women’s responsibility. If the hunters had to travel some distance to where a herd had migrated, the men did the butchering and carried the hide and meat back to camp, where the women waited for their return.

After they scraped the hide, the women pegged it flat to the ground or laced it to a four-sided frame that was set up vertically. The hide was then put aside until the women had time to work with it. The meat was cut up for boiling or sliced into strips and dried into jerky, or pounded to make pemmican. Pemmican was a winter staple that was processed by mixing pounded meat with melted buffalo fat, marrow, pinenuts, and berries.

The massive buffalo hides were either made into rawhide for tying all kinds of equipment together or they were tanned. Being an expert tanner was regarded as one of the most prized skills among women. Plains Indian women tanned each hide using a time-consuming process depending on what the hide was going to be used for. Hides that had been tanned with the hair on were used as bedding or robes; these hides were usually harvested in the fall or winter when the hair was the thickest. The women fashioned hides with the hair removed into various articles of clothing, lodge furniture, carrying cases, and tipi coverings. Buffalo hair was woven into rope or used to stuff various items such as cradleboards and headrests. Depending on the size of the tipi, it took one dozen to two dozen hides to make a tipi covering. Plains Indian women saved up tanned hides until they had enough hides to sew together to cover the tipi poles. The men furnished the hides and the poles which supported the tipi, but in terms of property, the tipi was hers, and she took pride in tanning and decorating the tipi covering.

The buffalo was the commissary of the Plains Indians, and virtually nothing was wasted. Buffalo bones and horns were fashioned into cooking utensils and tools, and even the hoofs were utilized in making glue. In truth, during the height of hunting season, even the most industrious Plains Indian woman could not keep up with her daily tasks and all the work that needed to be done to process the buffalo. It took the labor of at least two women to keep up with the amount of meat and hides one hunter provided. Usually, every wife had someone to help her – a young girl, an elderly relative, or additional wives in those tribes that practiced polygamy.

Gathering, Gardening, and Seasonal Harvests

Plains Indian culture was one of hunters and gatherers: the men did the hunting and the women did the gathering. The task of gathering and the preparation of the seeds, berries, and edible plants belonged to the women. They continually gathered supplies of food throughout the spring, summer, and fall to sustain their families when food was scarce during the cold winter months. In some areas where tribes lived in semi-permanent villages, the women planted gardens in the early spring to supplement the wild plants they gathered around the countryside. They discovered that seeds from procured plants could be grown in their encampment, and knowledge of soaking seeds to quicken germination was passed from tribe to tribe. The women started the plants indoors, then transplanted them outside when the weather permitted. In some tribes, men tended the gardens, but generally the women tended their gardens throughout the summer, while other tribes waited until the gardens were established and then picked up camp, traveling throughout the summer hunting and gathering. When they returned in the fall, the garden was harvested and the produce was added to their storage of food.

Plains Indian women supplemented their family’s basic diet of buffalo meat with a variety of wild berries, which were also an essential ingredient in making pemmican. Picking season began in late spring and continued throughout the summer. The women gathered in groups to pick berries and used this time to visit with one another as they worked. Because a young woman was in the company of other women, berry-picking was one of the few times of the year a man could court a woman.

Following the path of their ancestors, early Plains Indian women passed on characteristics to look for in utilizing plants and roots to their daughters. The women’s knowledge of the vast array of wild plants, used for food and for various purposes such as pipe-smoking, dyes, incense, or medicines, was part of their realm. The women obtained honor and clout through their close relationship to food. Their important contribution to their families and large quantities of food improved their social standing in the community. In many Plains Indian tribes, the women had complete control of the food supply, and their status in the community depended to some extent on the manner in which women distributed their reserve of provisions. Generosity and hospitality were highly valued as requirements of sociability among the Plains Indians; they were also a necessary form of welfare. In the Indian culture, it was customary that as soon as a visitor entered one’s home, food was immediately offered, and a gift of food was usually given to the visitor to take home. On ceremonial occasions, the women took pride in preparing food to bring to the feast.

Healing and Spiritual Power of Medicine Women

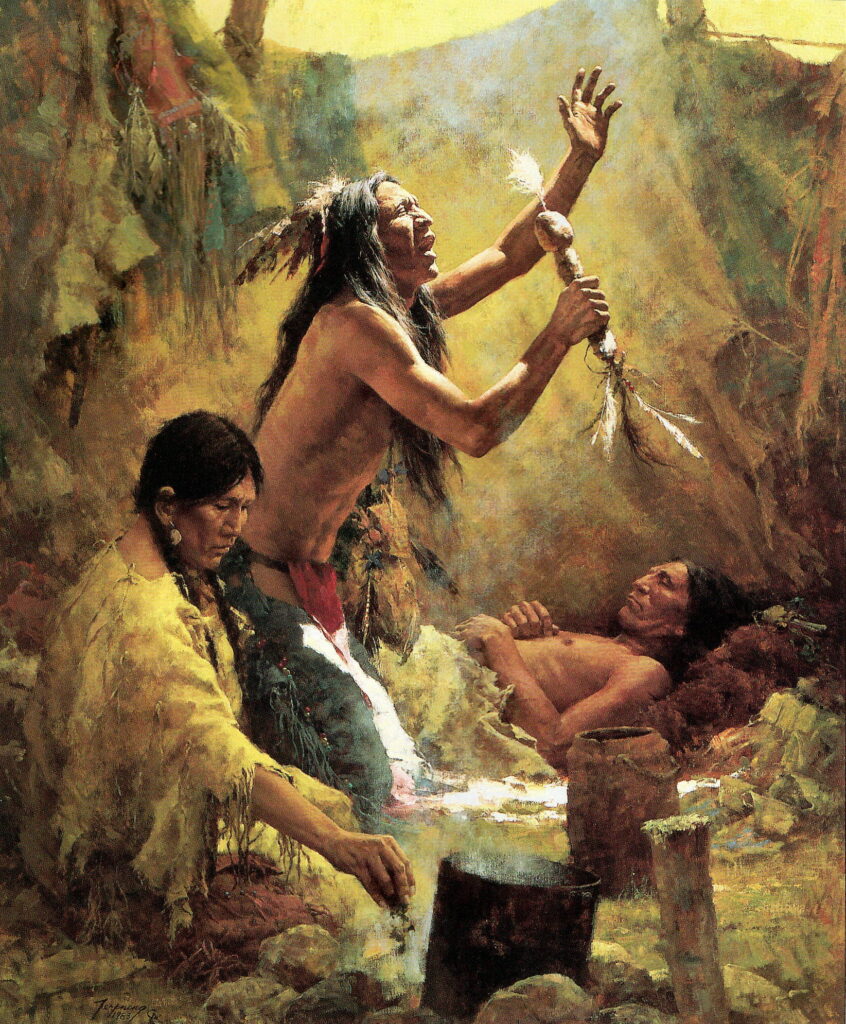

Plains Indians used various wild berries and herbal plants in ceremonial rites that celebrated the gift of life from Mother Earth and the continuation of its people. The women gathered herbal plants and stored them for seasoning or flavoring and for medicinal purposes in healing. The knowledge of herbal medicine was not confined to women, but generally women seemed to be more familiar with various herbal potions and brews. In some tribes, a woman – usually the wife of a medicine man – learned secrets in healing natural illness with herbs by assisting the medicine man. In other tribal communities, women learned the art of doctoring with herbs from their mothers and grandmothers. In general, if a woman inherited the right to become a medicine woman, her powers still had to be validated by a dream in which a spirit, in the form of a human, an animal, or perhaps just a voice, gave her personal knowledge. Women who had the gift for curing spent considerable time wandering around the areas surrounding their encampment, gathering herbs and other natural ingredients to prepare their medicines. In most Plains tribes, a medicine woman was not allowed to practice by herself until she reached middle age or older. The power to heal usually remained with a woman until her death.

(c)1984 The Greenwhich Workshop, Inc.

Like her male counterpart, a medicine woman was considered by early Plains Indians to have a special connection to the spirit world, and that link is what empowered her to heal. Emotional afflictions required supernatural remedies to recapture the soul. Generally, all healers called upon the aid of an ally from the spirit world to guide them in curing illnesses. Plains Indians believed that both physical and emotional illness reflect an imbalance between the natural world and the spirit world. A healer’s task was to restore harmony and balance using herbs, poultices, or spoken formulas.

In some tribes, women who acquired supernatural abilities became shamans. Shamans were believed to possess the power to influence the good and evil beings in the spirit world. A woman who wished to become a shaman usually sought training from an established shaman in her community. If the old shaman chose her as a successor, the younger woman took over the shaman’s position when she passed away. The new shaman used the songs and the formulas she inherited, as well as her own creations, to cure disease, predict the future, or control the weather. Plains Indian women gained respect and prestige by practicing medicine in their communities. The realm of medicine women in the culture of early Plains Indians was probably one of the women’s most powerful roles.

Artistic Expression and Craftsmanship

Plains Indians took much pleasure in finery, and when entire communities came together for various religious rituals and celebrations, which were a large part of their lives, they wore their best regalia. Plains Indian women took great pride in their family’s appearance, especially in the regalia of their husbands. It was a measure of status within the community to be recognized for ceremonial clothing at these traditional dances and feasts.

When not doing more immediate daily tasks, the Plains Indian women spent untold hours decorating clothing and accoutrements. The women fashioned ornaments and embellished clothing with brightly colored paints, quills, pieces of bone, shells, feathers, claws, and later with trade beads. The men, who were the primary beneficiaries of their wives’ labor, highly respected their domestic skills. In much the same manner that warriors tallied their coups and other war deeds, women kept count of their domestic accomplishments. In many tribes, women had societies where they would gather to work on their crafts and exchange techniques and ideas. Sometimes competitions were organized among the women, and winning a contest was similar to the honors won by their husbands for war deeds.

Women in Warfare and Defense

Although Plains Indian women were devoted to peace, and fighting battles with the enemy was generally the duty of the men, the women could not help but be involved in combat activities. When a war party was getting ready to go out on a raid, the camp was full of activity. For the most part, the women participated by providing supplies, outfitting their husbands for battle, singing in support of departing war parties, sending the warriors off with prayers for a safe return, and by imploring the warriors to avenge the deaths of those they loved. Sometimes young wives turned their children over to the grandmothers and accompanied their husbands on raids, helping out by preparing food, nursing the wounded, and when necessary, fighting beside the men. When the victorious war party returned from battle with their spoils, the women had the privilege of dancing during the victory celebration. In many early tribes, the fate of any captured enemy was decided by the women.

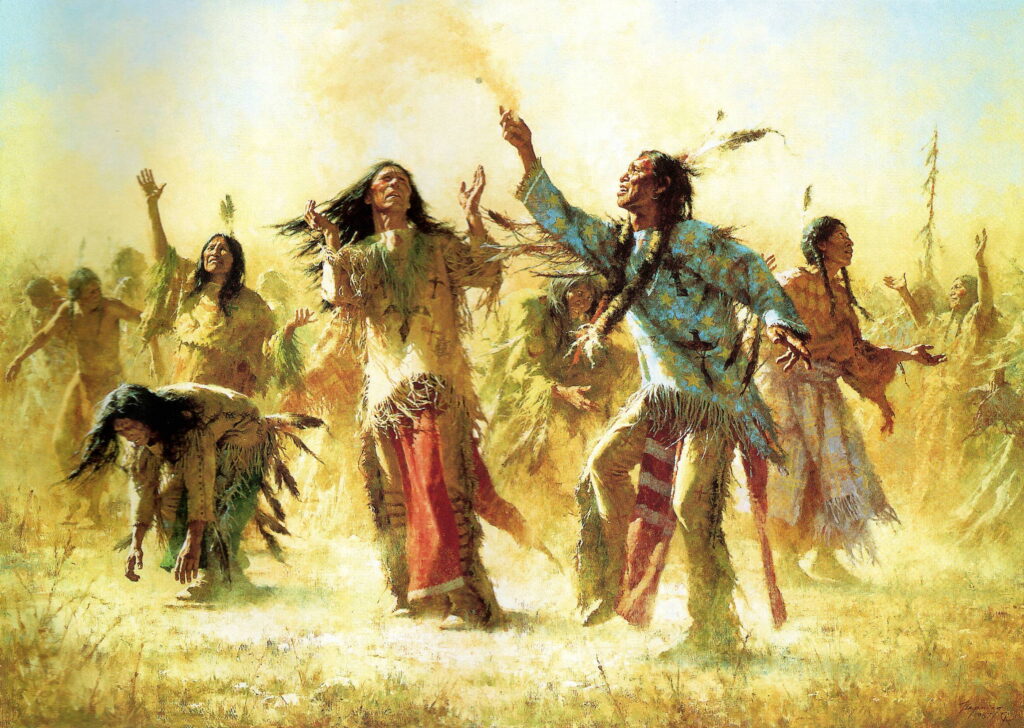

(c)1982 The Greenwhich Workshop, Inc.

In some communities, wives were allowed to carry their husband’s war shield on special occasions. The shield was perceived as having magical powers to protect the warrior in battle. A personal symbol of protection was painted on the cherished shield by the warrior and it was strapped onto the arm with which he held his bow so that his hands were free to use weapons.

It was the custom of Plains Indians to instill the virtue of bravery in both sexes from early childhood. In some cases, girls were encouraged to develop their riding and fighting skills. Ordinarily, the women left warring and raiding expeditions to men, but in some exceptional cases stronger stronger-willed women became outstanding warriors. Tribal legends give accounts of brave women who were cunning in strategy and skilled in archery and horsemanship. However, not all women who engaged in battle always had a choice. They joined the battle to save themselves and their children from death or from becoming spoils of war – taken from their homes and becoming captives of their enemies.

In some tribes, the women had societies whose members were mothers of warriors or women who had performed a heroic deed. The women in such societies generally joined the men of their tribe at the war council.

An appropriate way to express grief for women whose husbands had been killed in battle was for the widow to organize a vengeful raid on the enemy tribe. Sometimes the widow would be allowed to accompany the war party. Plains Indians followed certain rituals to show respect for the dead. An important custom for the women of many tribes was to mourn the death of their spouses for a year or longer. Widows in some Plains tribes cut their hair short, wailed, and slashed their bodies as a means of ensuring that dead mates would have a safe journey to the afterlife. In some Plains tribes, the family tipi was burned, and its contents were given away. The widow was taken in and cared for by members of her tribe. After the period of mourning, the widow usually remarried right away, for her skills were vital to the welfare of the community.

In the late 1800s, Plains Indian women joined the men of their tribes in dancing and chanting to bring the buffalo back and end the white man’s domination over their people. The ghost dance movement arose from a vision by a Paiute medicine man named Wovoka. In his vision, Wovoka was carried to the spirit world where departed ancestors were living a happy life. The men and women who participated in the ghost dance were inspired to die fighting for their hopeless dream of being saved and reunited with their departed ancestors. The ritual marked the final desperate attempt of Indian tribes in the United States to regain their old way of life.

Spiritual Life and Daily Prayer

Early Plains Indian women lived their lives in a world of ceremony and ritual. Although each season brought different rituals and social celebrations – held in thanksgiving for the gifts nature provided – the women perceived that every part of their universe possessed the forces of creation. Daily prayers were part of the women’s spiritual life. They continually prayed for blessings of good health for their families and other tribal members, for protection, and for a bountiful food supply. A woman’s prayers increased when her husband went on hunts and raiding expeditions, praying for success in his endeavors and for his safe return. Religion was an important facet in the lives of early Plains Indians. Spirituality gave them a deep sense of dignity and understanding for their surroundings.

(c)1988 The Greenwhich Workshop, Inc.

Wisdom of Elders and Preserving Tradition

The maturing Plains Indian women devoted themselves to daily prayer with the same reverent spirituality they had practiced as younger women. The end of childbearing years marked an important passage for women into a realm of respect and distinction. The women elders were valued for their wisdom and were regarded as the keepers of tribal history. As mothers were busy with the daily tasks of gathering and preparing food, a great deal of caring for the children, both boys and girls, was given to the grandmothers. The women elders instilled the ancient traditions, lore, and values of their people to their grandchildren. They helped their granddaughters master the traditional skills and crafts of their tribe. The maturing Plains Indian women completed the circle of their lives by guiding new generations in the path of their ancestors.

Honoring the Legacy of Native American Women

Early Plains Indian women were industrious with a love for children and family. Their role as wife and mother was highly respected by their tribes, and women were revered as the mothers of their race. In some tribes, women could also earn respect by obtaining positions of honor and power, such as skilled artisans or medicine women. But primarily, women worked in partnership with their husbands to survive the elements of nature and to provide sustenance for their families.

St. Stephens Indian Mission Foundation is a non-profit organization, incorporated under the laws of the State of Wyoming on March 31, 1974, and listed on page 184 of the 1993 OFFICIAL CATHOLIC DIRECTORY. The sole purpose of the foundation is “to extend financial support to St. Stephens Indian Mission and its various religious, charitable and educational programs and other services conducted primarily for the benefit of the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone Tribes on the Wind River Indian Reservation.”