June 24, 2022

This story was originally published by St. Stephens Indian Mission Foundation in VOL. XXIX APR/MAY/JUNE 1999 NO. 2. St. Stephens Indian Mission Foundation owns the copyright, and the story is reprinted here with permission from the Foundation. More information on the Foundation can be found following the story or by clicking on the link above.

During the cold, wintery months, when weather can make it difficult to travel, the people of the Wind River Reservation tend to stay close to home. But when spring arrives, there is renewed visiting among friends and family, an opportunity for increased family recreation and there are annual pow wows to attend.

Pow wows as we know them today did not always exist. It is believed that to the early Indian, these celebrations were summer gatherings of ceremonial and social dances, and warrior society dances held to honor and bring protection upon their members. But in its effort to prohibit “ghost dancing” among Plains Indians (a dance they believed would bring the buffalo back), the United States government banned some of their dance-traditions. When the ban was lifted in 1933, public dancing would once again be an active part of their lives.

Indian dancing has always played an important role in the culture of the Plains Indians, both spiritually and in secular life. Plains Indians have kept the tradition of the dance as a social get-together. Pow wows are the result of a great deal of planning and effort by many people. Both the Arapaho and Shoshone Pow Wow committees sponsor money-making projects held throughout the year to pay the expenses of putting on the festivities and to provide cash prizes for competition dancing. They reserve the summer months to hold pow wows and other special events, which include rodeos and annual Sun Dance ceremonies. The Sun Dance is a religious ceremony – a time of fasting and prayer – asking the Creator for special blessings upon the Indian peoples.

The origin of the term “pow wow” is difficult to determine. One theory suggests that Southern Plains Indians used the term in reference to American Indian gatherings and celebrations of song and dance. It is a known fact that these pow wows help keep the music and dance of the Native American alive for generations to come.

Pow wows are a time of celebration and gift giving and serve as a homecoming for the Arapaho and Shoshone people. Pow wows attract relatives and friends from all over the country and also bring dancers and spectators from other tribes to this reservation in central Wyoming. Visitors often stay at the pow wow grounds and encampments are generally pitched near the circular arbor. Hosting visitors from many tribes is an inherent part of the pow wow. As a courtesy, the host community will usually feed all visiting tribal members. This gathering of young and old alike is a place where people can relax and take the time to visit; a place where you can learn from one another.

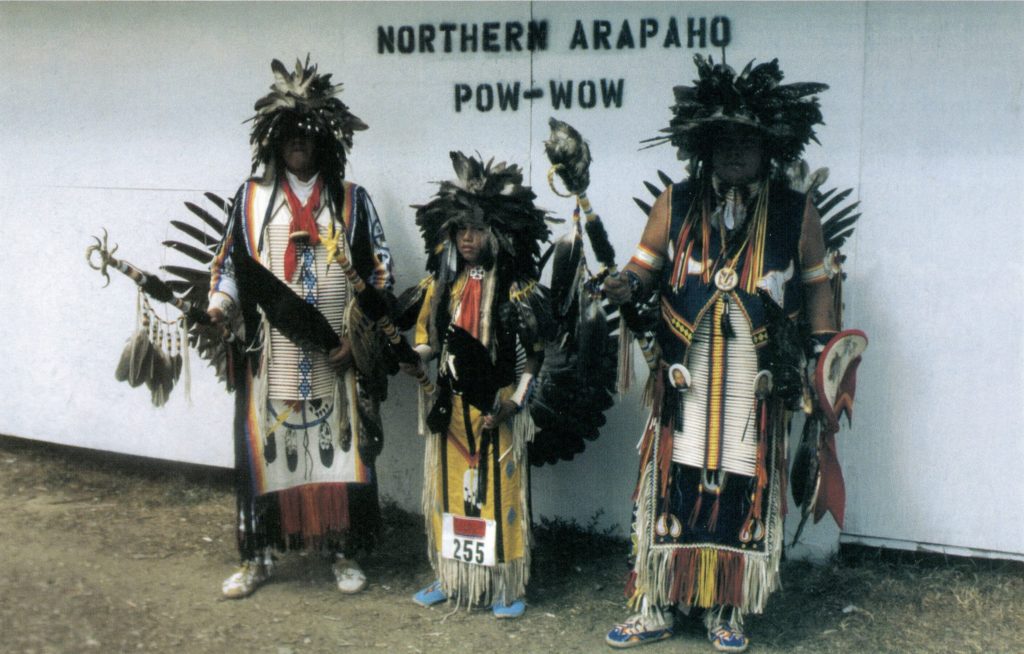

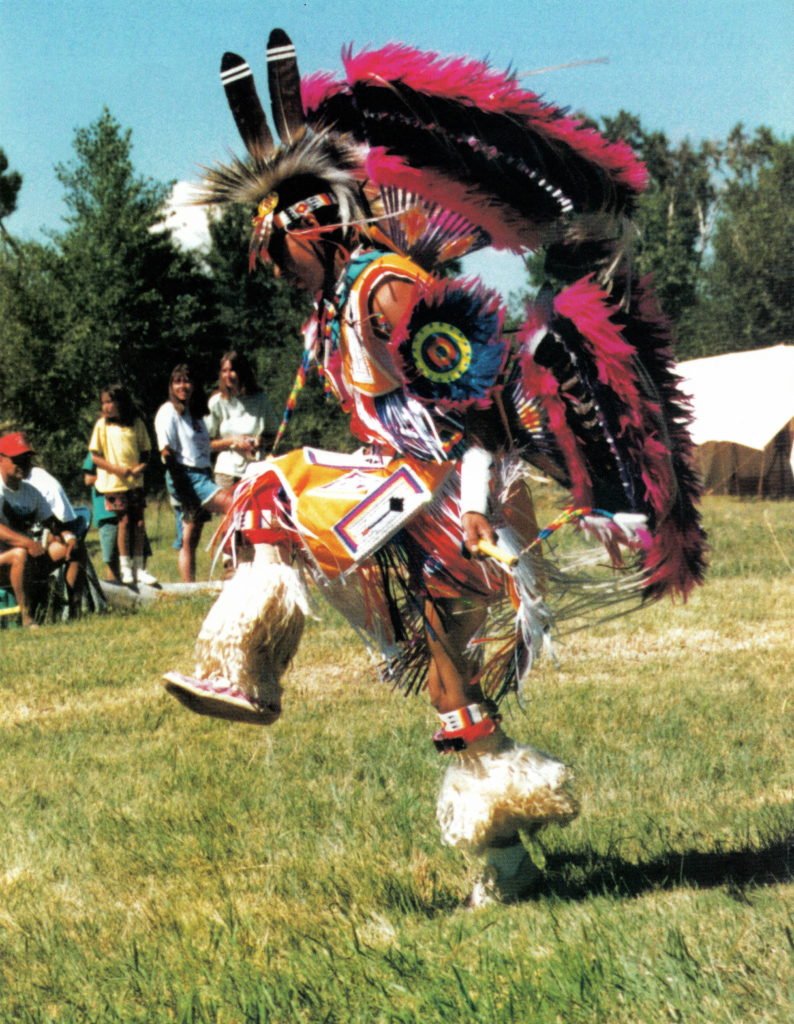

Daytime pow wow events include races, handgames, give-aways, visiting and other activities. The main dance events are scheduled for evening. Dancers can choose between two styles of dancing – traditional or fancy – in various categories for men, women and children. All pow wow participants enter the circular arbor during the “grand entry,” which is the opening ceremony honoring the color guard, veterans, pow wow royalty, dancers and elders. The first night is mainly inter-tribal dancing where everyone can dance. The children’s dance contests are held the second night and men’s and women’s fancy dance competitions are held on the third night. The contest judges, appointed by the pow wow committee, give points in each category for the dancer’s regalia, as well as for their performance.

A dancer’s performance is judged on style, timing and their ability to combine traditional aspects with personal attitude and individuality. Traditional dancers move with graceful, conservative steps and body movements. Fancy dancers have intricate footwork, spinning and head movement, and some deep bows. An imposing dignity emanates from men’s traditional and fancy dancers. Grace and pride radiates from women dancers.

The type of costume a dancer wears reflects the style in which they perform. Over the years, innovation in designs and clothing styles have been on-going. These stylistic changes in dance attire have evolved primarily because of the volume of dancers traveling to attend pow wows in various regions of this country and Canada. An item of clothing, headgear or hand-held object of a particular dancer from one tribe might catch the eye of a dancer from another tribe, who in turn, fashions a similar item for themselves. Thus, their regalia takes on a new appearance.

Much like the rodeo circuit, dancers travel from pow wow to pow wow to compete for cash prizes which offset their travel expenses and cost of their dance regalia. However, champion pow wow dancers can make a living from their talent. Competition dancing also helps draw public attention and participation to the pow wow circuit.

Contest dancing takes a good deal of a participant’s time in traveling, competing and the long hours it takes to fashion their hand-made attire. Ricky Blackburn, a 34 year old Northern Arapaho dancer, says that most dancers are brought up dancing as a family tradition, but he didn’t start dancing until two years ago. His son, Ricky, Jr., now nine years old, was encouraged to dance by his wife, Salome’s family from the time he could walk. Ricky says he always felt a sense of pride as he watched his son dance and now his four year old daughter, Jamay is dancing.

“I always liked to attend pow wows and watch the dancers when I was growing up,” said Ricky. “But I was more interested in participating in school sports and later on in community leagues.”

Dominic Littleshield encouraged Ricky to dance and loaned him one of his outfits. The loan of an outfit is very beneficial to a newcomer, it allows them to see if they like dancing prior to investing in the attire. “Feathers are held in high esteem in our culture,” said Ricky. “Loaning an outfit not being used honors the feathers.”

Ricky learned to dance by watching other dancers. “The first time I danced, I really caught on fire!” Ricky remarked. He credits Dominic Littleshield and Mark Soldier Wolf for encouraging him to continue dancing when he showed an interest. They have also helped him learn certain traditions and ceremonies. Ricky says he acquires a great deal of knowledge from listening to their many stories.

Ricky has three cloth dance outfits – two are fashioned with traditional featherwork, fans and bustles. His newest outfit is fashioned with Arapaho symbols that have special meaning to Ricky. The designs tell a story about his life: the two lightning bolts striking the top of a tipi represents the loss of a close playmate when lighting struck a nearby tree, killing his friend and burning Ricky’s feet; bear tracks honoring his grandfather, Basil Bears Backbone; the medicine wheel represents the four directions of travel; buffalo tracks honor the buffalo for all it gave to his ancestors; the Arapaho symbol for mountains is also used to represent a long and prosperous life; the circle represents the circle of life. A dancer’s dress attire expresses the individuality of each dancer, their personal heritage as well as individual taste. Design elements from a variety of traditional and modern sources are very common.

During the past two years, Ricky has enjoyed the hospitality of new friends while competing in pow wows throughout this region. When these new acquaintances attend dance contests at Wind River, Ricky and his family always return their hospitality. “Competition dancing always ends with a friendly word among the participants, there isn’t any animosity,” Ricky says. When he dances, Ricky is always conscious of some important advice: “Don’t dance for winning and losing. You can compete, but always remember why you dance – to honor yourself, your family, your people, and those who want to dance, but are unable to participate.”

The participation of men, women, children and elders makes the pow wow a family affair. Dominic Littleshield and his younger brother, Fergie attended local pow wows and danced occasionally when they were in elementary school. After graduating from high school, both had a desire to attend pow wows in different states. Their grandmother, Theresa, encouraged them to start dancing again so they could participate at these pow wows. Dominic said his grandmother danced when she was younger, but stopped dancing when her grandmother passed away and was laid to rest in Theresa’s dance outfit.

Dominic and Fergie have taken a great interest in dancing. Besides participating in pow wows, they also belong to a group of local dancers who are invited to perform for special events such as the recent “Heritage Tour” conducted by Martin Blackburn at St. Stephens Indian Mission. Before each dance show, they give the spectators an explanation of their attire and what type of dance steps they will perform.

Dominic and Fergie’s grandmother accompanies them as they travel to spring and summer pow wows in this region. Theresa has sewn her grandsons’ dance clothing for the past eighteen years. Dominic and Fergie design their own outfits and their grandmother does all the sewing and beadwork. Recently, Fergie’s wife, Regina started beading and now sews for their family.

Dominic says, “We dance because it’s a family activity that keeps us together. When we attend pow wows we meet old, as well as new friends that over a period of time are taken in as family.”

Some families will use the occasion of a pow wow to hold a “Give-Away” honoring a member’s notable achievement, a member’s participation in a pow wow, or the memory of one who has died. This custom goes back centuries when a tribal member would give away personal possessions such as food and hides to other members in appreciation for being honored for a skillful hunt or courage in battle. Today, the Give-Away dances might find a man presenting to a friend his favorite shirt or a woman offering her most precious beaded necklace. It is impressive to watch the sacrificial character of the Plains Indians as they share their possessions with relatives and friends.

The pagentry of a pow wow is known by both Indian and non-Indian alike as a time of skillful dancing, beautifully crafted dance outfits, music, Indian cuisine and booths containing Indian arts and crafts. It is an opportunity to experience American Indian traditions, dance and social customs first hand.

St. Stephens Indian Mission Foundation is a non-profit organization, incorporated under the laws of the State of Wyoming on March 31, 1974, and listed on page 184 of the 1993 OFFICIAL CATHOLIC DIRECTORY. The sole purpose of the foundation is “to extend financial support to St. Stephens Indian Mission and its various religious, charitable and educational programs and other services conducted primarily for the benefit of the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone Tribes on the Wind River Indian Reservation.”

Posted in Notes From the Field